박주애 Parkjuae: 박주애 Juae Park

원시인들에게 집을 짓는 것과 형상을 만드는 것 사이에는 아무런 차이가 없었다고 한다. 비바람을 막아주는 집과 비바람을 일으키는 정령을 물리쳐 줄 형상은 모두 자신을 지키기 위한 것이기 때문이다. 이처럼 예술은 원래 주술적인 목적으로 사용되었다. 시간을 거슬러 올라가면 갈수록 예술의 목적은 더욱 명확해지지만, 현재의 우리들에겐 생소해진다. 그러나 형상을 통해 주술적 의미를 다시 찾아내는 것은 지금도 그리 어려운 일이 아니다. 성상이나 불상, 부적이나 자신의 가족사진을 아무렇지 않게 훼손하는 사람은 없을 것이다. 예술의 주술적 의미를 이해하는 데 필요한 것은 인간이 전지전능하지 못하다는 것을 인정하고 불안한 현실에서 자신을 지탱해줄 ‘무언가’의 신비로운 힘을 아직 믿고 있느냐의 여부이다.

박주애는 이번 개인전에서 도자기와 그림을 선보인다. 2019년부터 도자기를 배웠던 그는 2020년부터 본격적으로 도자기 작품을 제작했다. 시험관 아기시술의 실패로 인한 고통스러운 상황 속에서 작가는 뭔가 새로운 것을 배우고 싶은 마음에 공방 수업을 듣기 시작했다. 의도한 것은 아니지만 임신과 연관된 형상을 원시 조각처럼 만들어 냈다. 이유는 당시 머릿속을 가득 채웠던 생각이 오로지 임신이었기 때문이라고 한다.

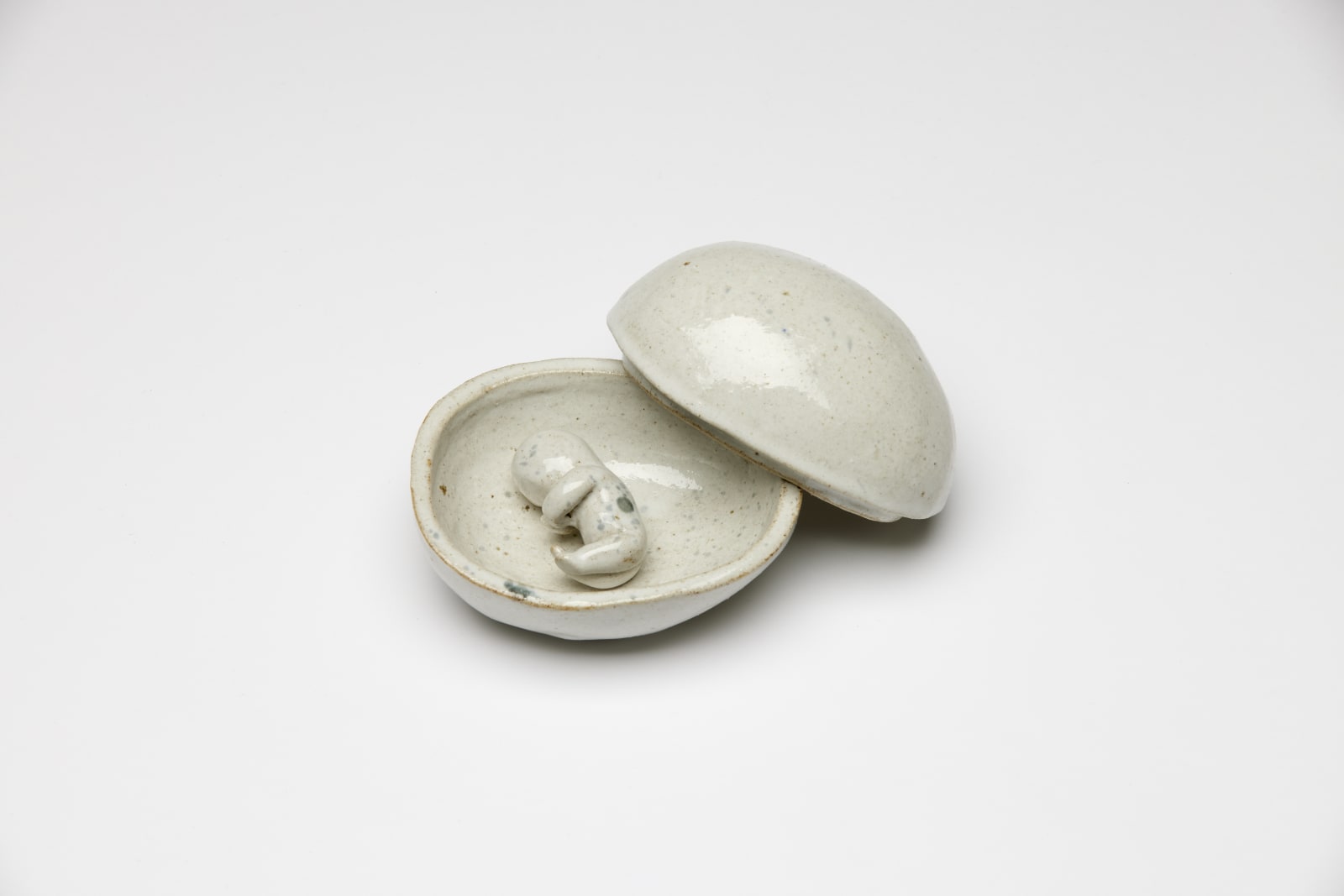

도자기 작품은 임신한 여성의 몸, 자궁, 태아, 모유가 나오는 가슴, 알의 형태를 보여준다. 박주애는 여성의 임신한 배가 마치 알처럼 보였다고 한다. 알은 그 안에 존재하는 생명체를 암시하기도 하며 겉으로는 아무렇지 않지만 안에서 뭔가 움직이고 탄생하는 상황을 은유한다. 도자기는 임신의 대리보충물이다. 대리보충은 우리가 욕망하는 것을 현전시키는데 필요한 ‘무언가’를 제공하지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 그 ‘무언가’는 욕망하는 대상 자체일 순 없다. 결국, 대리보충은 결핍을 상징한다. 그리고 결핍이 있는 곳이 바로 형상이 탄생하는 자리이다. 박주애는 임신이 되지 않는 상황에 대한 막연한 불안함을 떨쳐내는 한편 임신을 기원하는 마음으로 일주일에 하나에서 두 개씩 도자기를 만들었다고 한다. 그의 도자기는 유희와 진지함이 복잡하게 결합된 오브제이다. 희망과 비애, 신비한 황홀과 불안, 기쁨과 슬픔이 양가적으로 뒤섞여 있다.

박주애는 도자기를 만들 듯 그림을 그렸다. 평소 도자기를 만들기 전에 드로잉을 먼저 제작한다고 한다. 평면(드로잉)에서 오브제(도자기) 그리고 다시 평면(그림)으로 돌아간 것이다. 그러니 이미지가 없었다면 오브제도 없었다. 처음에는 형상을 직관적으로 표현했지만, 작업을 진행하는 과정에서 임신에 대한 욕구와 불안함이 다소 옅어 지면서 형상은 은유적으로 변화한다. 추상화된 태아의 성장 과정, 탯줄, 난소, 난자, 여성의 몸이 그림의 요소가 되어 화면 위를 유영한다.

몸은 당연한 것처럼 보인다. 그러다가도 우리의 눈에 자신의 몸보다 신비한 것이 없다. 몸의 진화, 성, 인종, 탄생과 죽음, 노화, 장애, 질병 등 몸에 대한 모든 담론은 사회적이면서 또한 지극히 개인적이다. 어떠한 몸도 이 문제들로부터 벗어날 수 없다. 몸의 문제로부터 자유로울 수 있는 존재는 젊고 아름답고 늙지 않고 병들지 않는 완벽한 몸을 소유한 인간일 것이다. 하지만 그것은 우리에게 아직도 먼 이야기이다. 몸의 한계를 느낀 인간은 자신의 몸을 자연에 반하는 상태로 만들어 놓는다. 그런데 노화를 지연시키고 몸의 형태를 변형하고 의학 기술로 신체적 기능 향상시키는 이 유토피아적 기획의 대가는 오히려 자신의 약점을 자각한다는 것이다.

박주애는 자신이 얼마큼 절실했는지 진심을 표현하고 싶었다고 한다. 사실 작가에게 결핍과 불안은 언제나 작업의 영감이 되었다. 작품을 통해 자신의 결핍과 불안을 노골적으로 드러내는 것이 삶과 예술을 연결하는 작가 나름의 방식인 것이다. 그의 도자기와 그림은 자기 연민과 간절함을 적절히 섞은 사랑스럽고 유머러스한 결과물이다. 작품에서 드러난 노골적인 신체는 형태적인 유희가 아닌 솔직한 폭로와 가감 없는 욕망의 발현에 가깝다. 내면의 밑바닥에서 나온 그 어떤 이미지가 작가의 절실한 SOS가 아닐 수 있을까. 그 이미지는 어떻게든 현실로부터 해방되는 길을 찾는다. 우리 눈에 공상과 근거 없는 환상으로 보이는 그의 작품에 바로 한 인간의 비애와 애원이 있다.

Building a dwelling and creating an object with form were not always distinguished from one another in prehistoric times. The safety offered by permanent barriers to elements were not entirely without parallels to the security and auspiciousness delivered by formed images. As such, the purpose of art was tied to shamanic practices. This purposefulness of art is increasingly self-evident further into the past, but quite obscure in our present. However, reestablishing that shamanic connection through imagery is not a difficult task, even today. People generally do not vandalize Christian icons or Buddhist shrines, felicitous talismans or family photos. Comprehending the shamanic underpinnings of art first depends on the acceptance that we are neither omniscient nor omnipotent, and as a consequence have faith in a mystical force that will aid and sustain us through the fog of uncertainty.

In her latest solo exhibition, Juae Park presents ceramic works and paintings. Park began to work with earthenware in 2019 and introduced them into her oeuvre in 2020. It initially began when an in-vitro fertilization effort with her partner failed and left her in great distress. She had taken up learning something new as a foil for her emotional state. Although not intended, she created shapes associated with pregnancy, similar to the rudimentary forms found in primitive sculpture. Park explains that it was all she could think of: pregnancy.

The earthenware takes various related forms: pregnant mother’s body, uterus, fetus, lactating breasts, and an egg. To Park, a pregnant abdomen looked like an egg. Eggs have become a symbol of the life within, as well as a metaphor for gestation and being carried to term. The earthenware are supplément to pregnancy. Suppléments provide something necessary as substrates to our desire, but it is not subject of desire itself. That is, supplément means there is something wanting. And it is in wanting where imagery is born. As the artist struggled with the failure to conceive, she crafted one or two earthenware each week to shake off the looming anxiety and wish for auspiciousness. Her earthenware are objects that intricately combine play and earnestness, ambivalently blending hope and sorrow, esoteric ecstasy and anxiety, joy and sorrow.

Juae Park’s paintings were drawn in the style of her earthenware. Usually when she makes her earthenware, she first draws it. In a sense, she has taken it from the plane (drawing) to the object (earthenware) and then back to the plane (painting). So without imagery, there would not have been objects. At first, she gave the forms an intuitive expression, but as she continued to work on the forms, her initial desire and anxiety surrounding pregnancy became more metaphorical and less intense. The gestation of the abstracted fetus, umbilical cord, ovaries, eggs, and female bodies all became parts floating in the frames of her painting.

The body seems natural. One might say there is nothing more mysterious to our own eyes than ourselves; our bodies. All our discourse on the evolution of the body, sex, race, birth and death, senescence, disability, and disease, are extremely social and simultaneously deeply personal. Nobody is free from these problems. Anybody who is free from these problems will need to be have the blessing of youth, a favorable appearance, and a perfectly unaging, unailing physiology. It is close enough to be imaginable, but far enough to be a story. Once we experience the limits of our body, we understand our body to be something that runs against the grains of nature. However, this utopian pursuit to delay aging, attain plastic perfection, and augment the body with medical technology was costly. It signified an awareness of one’s own wanting.

Juae Park wanted to sincerely convey the desperation she was swimming against. In fact, the wanting lack and anxiety have always served as inspirations to her artistic practice, where her mode became the candid unveiling of her own dearth and anxieties through art. Her earthenware and paintings are loveable and humorous, blending humor with pity for herself. The anatomically correct depictions of her earthenware are not a play on form, but a genuine disclosure and expression of desire. What of her creations would not be a desperate plea when all of the images have been drawn from the bottom of her inner self? That image seeks emancipation from reality, no matter what the cost. As her works are fantastic and illusionary, they also embody her sorrow and desperate pleas.