용 룡 Yong Ryong: 손동현 Donghyun Son

손동현의 개인전 《용 룡》은 문자가 구성되는 체계에 대한 독해를 통해 ‘용(龍)’의 형태에서 공간으로서의 구조를 발견하고, 이를 화면 위에 펼쳐낸 회화를 선보인다. 손동현은 한국화의 방법론과 대중문화의 이미지를 결합해 오늘날 회화가 점유할 수 있는 유효한 그리기의 과정을 탐구해 왔다. 이번 전시는 그간 손동현이 산수, 인물 등 전통회화의 소재부터 만화, 브랜드 로고 등 대중적인 이미지를 그림의 대상으로 삼은 일에서 나아가, 문자를 활용한 회화인 ‘문자도’의 방식에 집중한다. 특히 하나의 문자 ‘용(龍)’을 중심으로 자전에 등장하는 여러 형태의 서체를 분석하고 분해해, 평면의 회화 안에 구성되는 다양한 공간의 모습을 상상한다.

용은 동아시아를 비롯해 서구를 포함한 전 세계의 지형에서 수많은 상징적 이미지로 소환된 대상이다. 여기서 말하는 상징적 이미지로서의 용이란, 먼 과거부터 지금까지 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 소설, 만화, 영화 등 문학과 대중문화의 주요 대상이 되어 온 용의 특성이 있음을 의미한다. 일례로 동아시아에서 용은 왕실의 고귀함을 상징하거나 농경사회의 날씨를 관장하는 신으로 여겨지기도 했으며, 〈드래곤볼〉 등 일본의 대표적인 만화에서는 소원을 들어주는 신비로운 동물 역할이기도 했다. 그런 반면 서구에서 용은 주로 공주를 납치하는 악역이거나 금은보화에 욕심이 많은 사악한 존재로 이해되었다. 즉 용은 그것이 등장하는 서사가 언제, 어디서 펼쳐진 것이냐에 따라 여러 갈래의 의미로 나타나면서 ‘이야기’를 만들고 소비하는 문화 속에서 스스로의 이미지를 끊임없이 재생산해 왔다. 한편, 이러한 용의 다채로운 이미지 가운데 일맥상통하는 한 가지 특징이 있는데, 바로 용이 상상의 동물이라는 점이다. 동아시아 불교의 ‘십이지신’ 중에서도 유일하게 실존하지 않는 동물이기도 한 용은 현실을 넘어 꾸며진 무수한 이야기를 발동시킨다.

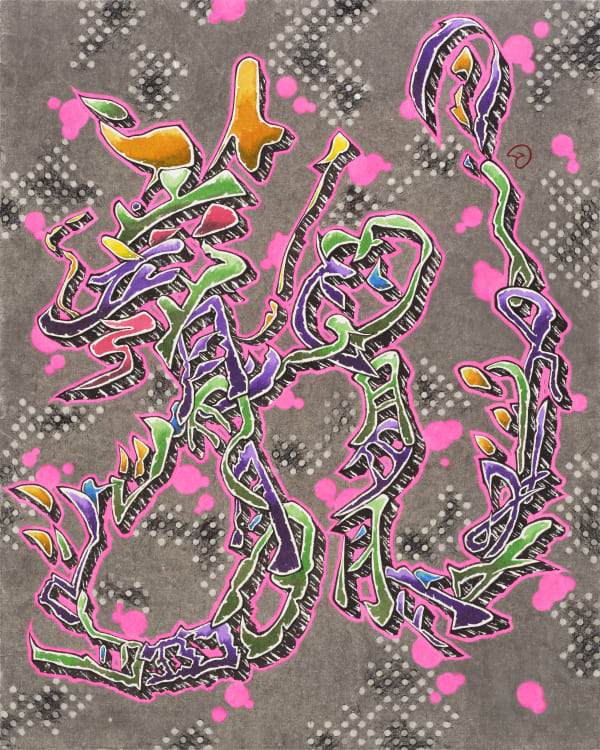

손동현은 이처럼 용을 둘러싸고 시대와 지형을 교차해 현재의 시간 위에 솟아난 상상들의 현현 자체에 주목해 ‘龍’의 형태를 관찰한다. 그가 작업의 출발로 삼은 것은 과거의 여러 인물이 남긴 한자를 모은 서예자전(書藝字典)과 전각자전(篆刻字典)이다. 부수(部首)에 따라 목차가 구성된 두 자전은 전서, 예서, 초서 등 다양한 자형으로 쓰이고 새겨진 한자를 나열한 서체의 책으로, 한자의 뜻이나 역사 풀이가 아니라 말 그대로 형태의 나열이 중심인 서적이다. 이를 토대로 손동현은 문자 하나를 파자했을 때 드러나는 작은 글자들, 문자를 쓴 사람에 의해 달라지는 전체 모양, 각각의 획이 뻗어가고 흘러간 모양 등 독립된 문자에 담긴 세부 요소를 파헤친다. 이후 세밀하게 쪼개어 파악한 문자의 온전한 모습을 다시 떠올리며 미시적인 요소들이 뭉쳐 만들어진 단 하나의 모양으로서 문자의 형태를 파악해 나간다. 예를 들어 ‘龍’을 해체해 설 립(立), 달 월(月) 같은 구성 요소를 서로 다른 화폭에 그리거나 한 화폭에서 면을 분할해 각각 그려 넣고, 여러 형태의 ‘龍’에서 가져온 문자를 하나의 화폭에 구성하는 식이다.

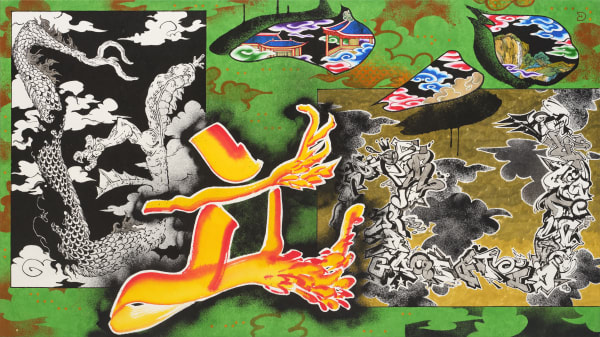

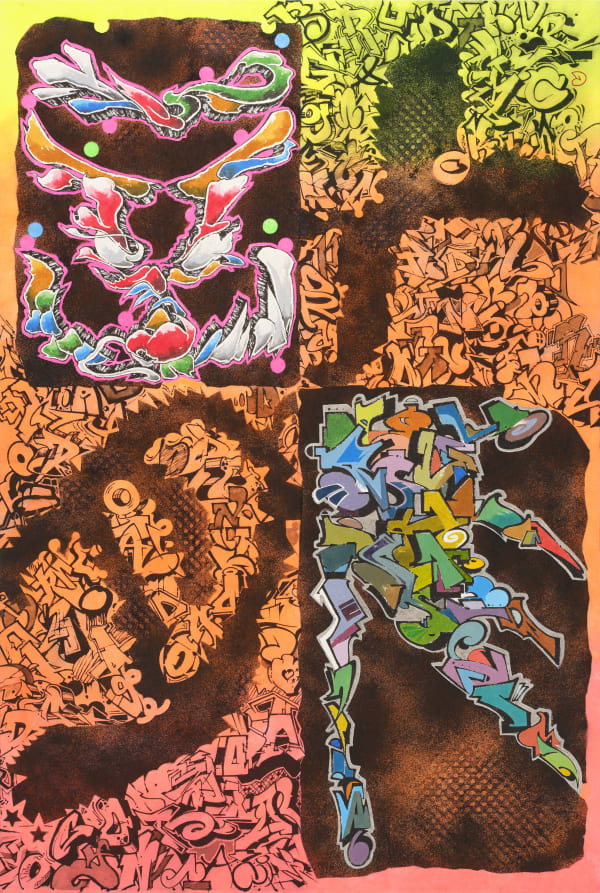

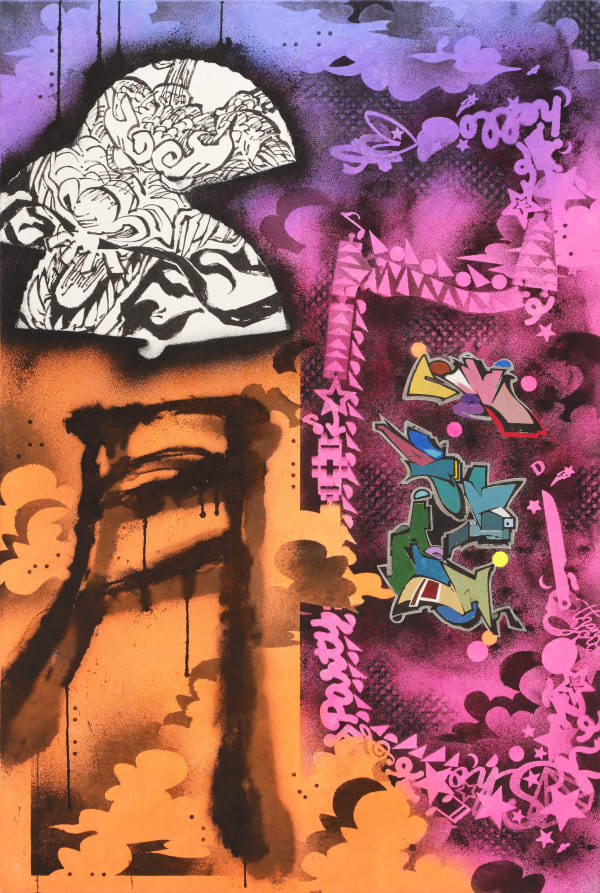

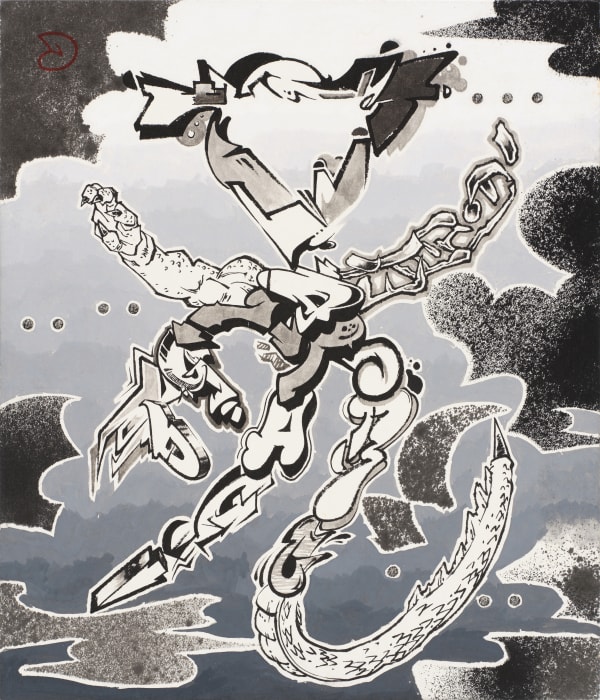

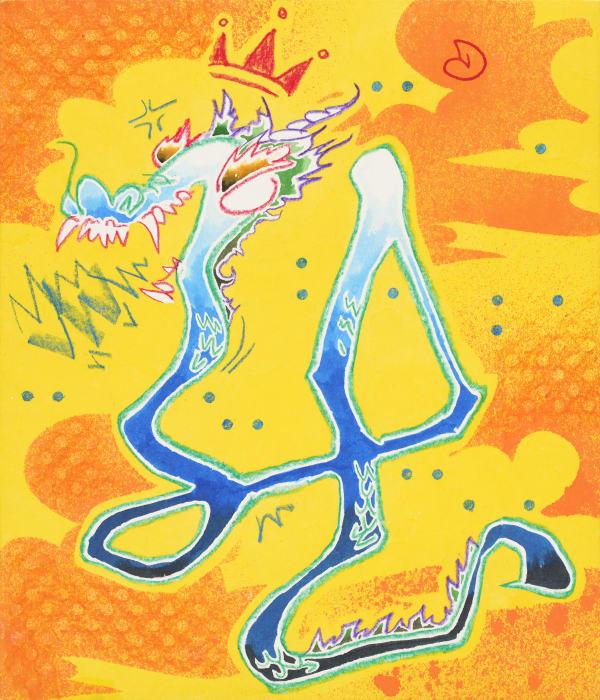

‘용(龍)’은 문자를 분해하고, 흩어내고, 다시 결합시켜 문자가 지닌 공간으로서의 특성을 이해하고자 하는 손동현의 그리기 방법론과 유사한 구조를 취한다. 오늘날의 한자 ‘龍’은 존재하는 글자를 조합해 존재하지 않는 것의 모습을 상상한 결과다. 즉 ‘龍’은 각각 구체적인 의미를 가진 개별 한자가 복합적으로 엮인 문자로, ‘龍’이라는 문자 하나에는 복수의 공간이 내재한다고 볼 수 있다. 이러한 ‘龍’의 특징처럼, 손동현이 다룬 화폭에는 ‘龍’이 흩어지거나 합쳐지며 얕고, 깊고, 좁고, 넓은 면들, 달리 말해 ‘공간’이 솟아난다. 이에 더해 전통적인 수묵 기법에 잉크, 아크릴릭 잉크 등의 현대적인 재료, 영문 타이포그래피를 중심으로 이루어진 그래피티 방식, 일상적인 사물을 활용한 스텐실 등의 표현들이 화면 곳곳에서 독자적으로, 혹은 융합되어 나타나며 화폭의 공간을 더욱 복잡하게 분해한다. 또한 ‘용’의 이미지, ‘龍’의 형태를 해체해 머리부터 꼬리까지 이어 붙인 화첩, 화폭 주변 벽과 부채에 펼친 구름(雲)은 ‘용’을 구성하는 부차적인 요소까지 결합한 화면으로서 확장된 공간을 만든다.

손동현이 ‘용(龍)’을 그리는 일에는 용을 어떻게 표현할 것인가의 문제보다 용이라는 문자가 지닌 복합적인 구조와 역사를 어떻게 바라볼 것인가의 문제가 녹아 있다. 그림으로 사물을 나타낸 체계인 상형 문자에서 시작한 ‘龍’은 ‘용’에 부여된 뜻과 개념을 나타낸 표의 문자로 변화하며 지금의 형태를 완성했다. 손동현에게 ‘용(龍)’은 단순히 의미를 전달하는 수단으로서의 문자를 넘어, 시대에 따라 그것의 모양에 담긴 변화들, 이를테면 ‘용’에 대한 인식의 전환, 형태적 변모가 적용된 대상인 것이다. 그리고 이러한 변화와 적용의 과정은 그가 주로 다루는 매체인 한국화가 동시대의 지평에서 지니는 의의를 탐구해 나가는 자신의 일과 닮았다. 한자를 만든 동아시아 문화가 존재하지 않는 동물을 상상해 문자를 부여해 온 방식은, 지금의 시간에서 한국화가 태동 이후 겪어 온 격변의 시간들을 함축하는 것인지도 모른다.

Donghyun Son’s solo exhibition Yong Ryong presents paintings that discover the structure of space in the form of the dragon (龍), a comprehensive reading of how the its constituent radicals unfold on paper. By combining the methodology of Korean painting with images from popular culture, Donghyun Son has been exploring procedural spaces that painting can occupy today. Previous to this exhibition, these spaces existed across styles of traditional sansuhwa (山水畵: idealized brush-and-ink paintings of mountains with a body of water in the foreground) character portraits, and East Asian ink-wash paintings of cartoon, brand logos, and other popular images. For this exhibition, the space has shifted to munjado (文字圖: calligraphic character-painting) of the SinoKorean character Ryong (龍: the dragon of the Orient), singularly analyzed and deconstructed in the various radicals as the character appears in the jajeon (字典: dictionary of chinese characters), imaginatively expositing into painterly spaces.

The image of the dragon has been invoked across the world from the East to the West, in numerous symbolic forms. The dragon is a symbol in the sense that it is conjured with certain recurring proto characteristics across records and literature in the distant past to aspects of popular culture, including novels, comics, and movies in the present. In East Asia, dragons often symbolized the noble status of royalty. In those agricultural societies, dragons were deities with power over meteorological conditions. In the iconic Japanese manga series Dragon Ball, the dragon is a mystical god-like figure with supernatural wish-granting powers. In the West, dragons were more often understood as sinister beings, villainous scaled kidnappers of princesses and infamous hoarders of gold and other treasures. With many shades in-between, the dragon has taken on various associations and variegated meanings depending on when and where its narrative unfolded. Auspicious or treacherous, one character was true about the dragon, wherever its narrative unfurled and uncoiled itself: the dragon was a fantastic being. Even among the Twelve Spirit Generals of the Buddhist calendar, the dragon was the only fictive, fabled creature.

Donghyun Son scrutinizes the calligraphic form of 龍 through the imagined and evident manifestation made tangible across centuries and borders. Son is informed by the Seoyae-Jajeon (書藝字典-Dictionary of Calligraphic Styles) and Jeongak-Jajeon (篆刻字典-Dictionary of Seal Carving) which are collections of calligraphic characters left by past masters. Both references’ table of contents show an organization scheme based on the characters’ busu (部首-constituent radicals), each presented with varied styles such as the jeonseo (篆書-seal script), yaeseo (隸書-clerical script) , haeseo (楷書-regular script), haengseo(行書-running-cursive script), and choseo (草書-cursive script). The dictionaries are not concerned with etymologies or semantics and only with the typographies of the character-form. Following the references, Donghyun Son dismantles the dragon into constituent radicals, each with idiosyncratic patterns of entrance, under-overturns, ovals, ascending movements, and ink flow. The constituent parts are reimagined into a whole character that contains all its components. In the case of the character 龍 for dragon in this exhibition, radicals of lib (立-to stand) and weol (月-the moon) are separately composed upon separate papers canvases, but with multiple typographical styles on a single sheet.

龍 as a calligraphic form somewhat mirrors the artist’s calligraphic methodology which is to understand the character’s spatial essence through deconstruction, scattering, and reunification. The yong-ryong (龍) character denotes a fictive idea, but the character itself is compound of essences—radicals—that denote real and tangible things. As the character is a composite of radicals, each with their own space-meanings, the character is possibly also a composite of spaces. Some spaces are thin, narrow, broad, or even deep. Furthermore, the artist’s choice of modern materials such as acrylic and other inks, used with traditional sumuk (水墨) ink-wash techniques, English typographic graffiti methods, and mundane object-stencils add a complex layer that demarks and unites the space. The image of the dragon, captured in logographical form of the calligraphic 龍, attached from head to tail in radical-form, as well as the woon (雲-cloud) on the nearby walls and fans populate the space as enriching, complementary elements to the space.

The question p osed by Donghyun Son i s n ot a bout the dragon’s r epresentation, but about the appropriate viewing of the character’s complex structure and history. The logographic-ideographic hints of 龍 give insight to the given meaning of the dragon and morphological process, an archival aspect that contains meaningful diachronic change in perspective and form. This process of change and adaptation mirrors Son’s own artistic practice of exploring the meaning of Korean painting, his primary medium, in the contemporary horizon. And in the way East Asian cultures understood the possibility of the fantastical dragon and manifested it through radicals and characters, perhaps there is another layer of metaphor between Donghyun Son’s dragon and the chimeral history of Korean painting that has hardly known a day of calm since the earliest of its days.