최기석 개인전: 최기석 Kiseog Choi

20세기 모더니즘 미술은 예술의 자율성을 강조하며 예술 장르 간의 경계를 구분했다. 조각의 주제를 최소화하고 환영을 불러일으키는 요소를 추방한 모더니즘 조각은 작품 안에 이야기나 주제를 담는 것을 퇴조의 징후로 보았다. 그런데 현재에도 이런 모더니즘 조각의 강령이 유효할까. 예술의 순수성을 여전히 존중하기는 하지만 현대 조각은 회화와 조각, 조각과 건축 등 장르 간의 경계를 허물고 있으며 작품 안에 직관과 감성을 담거나 수작업의 정서를 여전히 전달한다. 최기석의 조각은 자연석처럼 자연에 풍화된 철의 표면과 기하학적 구조를 통해 관람자의 신체적, 정서적 반응을 불러일으킨다. 그리고 그의 드로잉은 종이가 더는 종이가 아닌 철의 표면을 은유한다. 모더니즘 조각이 말한 중성적이고 이성적인 존재로 남기에 조각은 너무 많은 것을 이미 암시한다.

그동안 최기석은 철을 녹이는 용접 방식과 두드리거나 누르는 단조 방식을 통해 변형된 철의 표면을 탐구해 왔다. 35년간의 일이었다. 이번 갤러리2 개인전에서 그는 철을 있는 그대로의 상태로 보여준다. 작가는 철을 ‘원래’의 자리로 돌려놓고 싶었다고 한다. 가공하지 않은 그저 존재하는 그대로의 가장 기본적인 상태로 말이다. 구조는 구축하되 철의 표면은 손상시키지 말 것. 용접이나 단조 방식이 아닌 철판을 조립하는 방식은 철의 표면이 가장 덜 손상되는 방법이었기 때문이다.

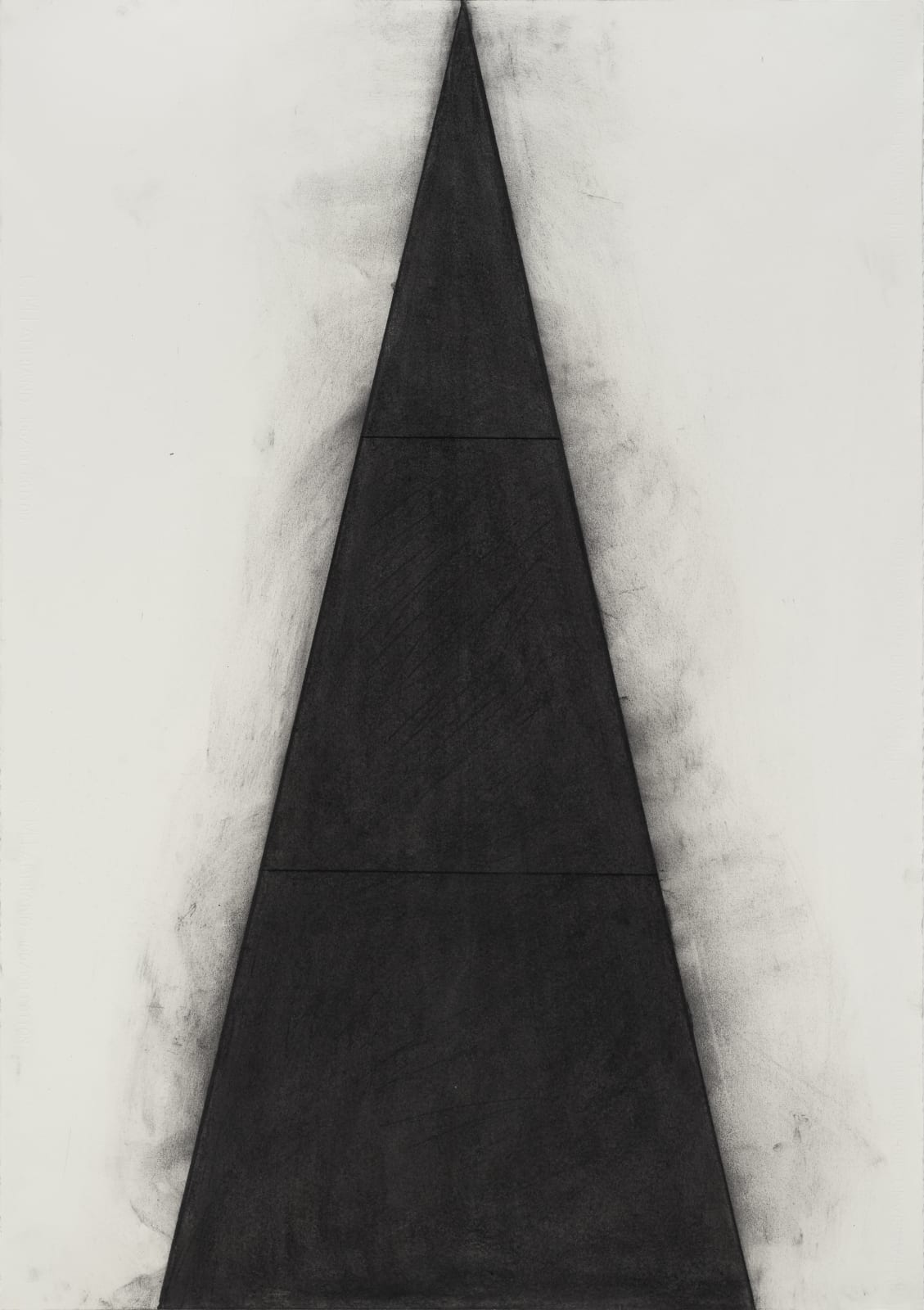

작가는 이번 전시에서 처음으로 드로잉을 전시한다. 조각 작업에 들어가기에 앞서 그는 마치 설계도를 그리듯 드로잉을 제작했다고 한다. 단순한 구도와 무심한 여백은 최기석의 조각을 연상시키지만, 색채의 번짐과 흑과 백의 대비는 조각과 다르게 평면 매체가 갖는 물리적 특성을 드러낸다. 그는 드로잉이 ‘자연스러운 부산물’이길 원한다고 말한다. 종이 위에 목탄을 반복적으로 칠하고 뭉개는 과정을 통해 드로잉은 철의 무게감과 밀도를 그대로 전달한다. 색이 칠해진 면은 철판의 질감을 떠올리게 한다. 드로잉은 이미지를 종이 위에 그렸다기보다 종이라는 물질을 철판으로 변화시킨 듯하다. 지극히 조각가다운 드로잉이다.

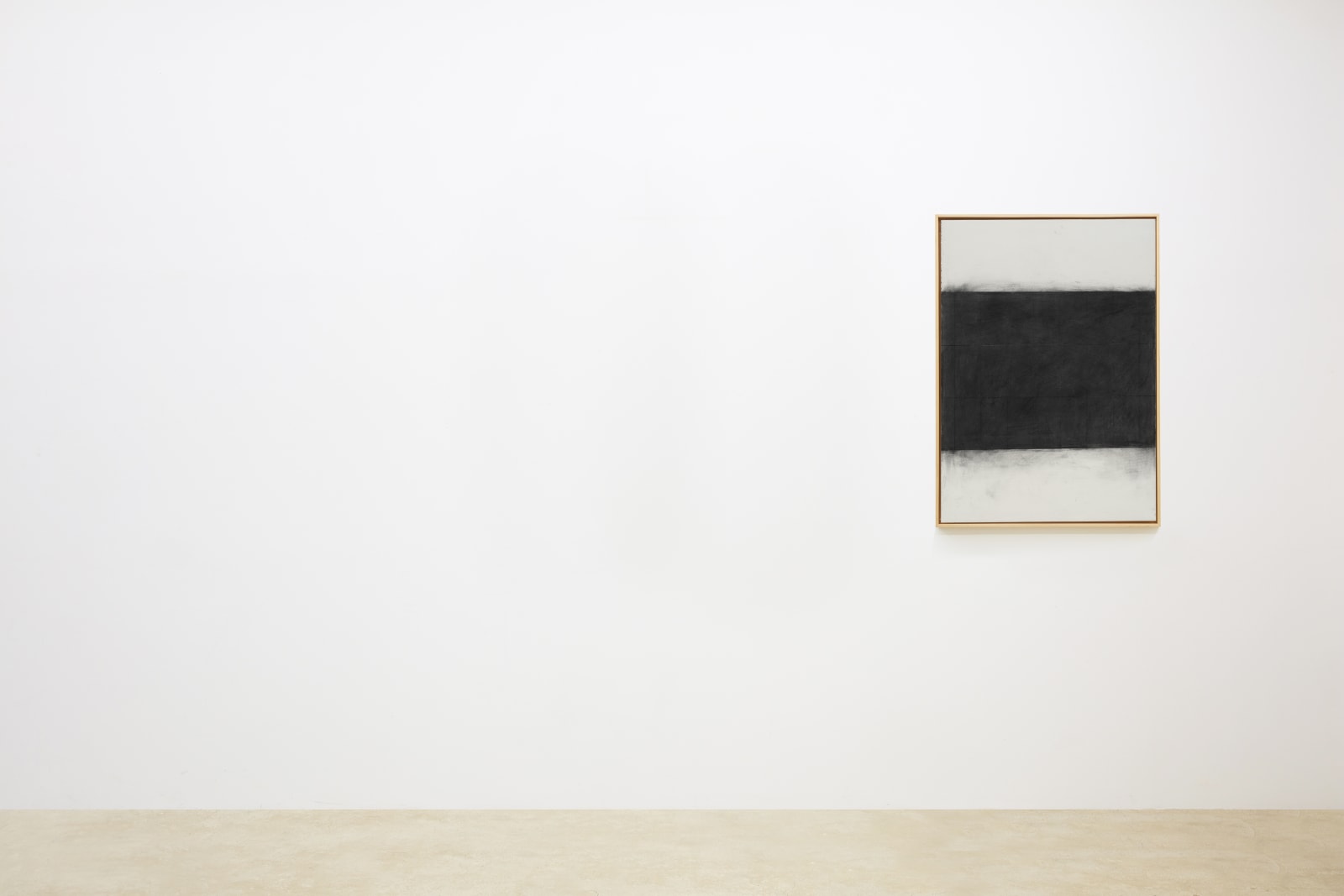

두 개의 공간으로 나눠진 전시장에는 밑면이 240cm, 높이 360cm의 삼각뿔 형태의 조각과 폭 240cm, 너비 480cm, 높이 360cm의 직사각형 형태의 조각이 각각 설치되어 있다. 철의 표면은 관자의 시야 전체를 덮는다. 압도한다. 작품의 크기와 형태는 전시 공간의 물리적인 조건을 반영한다. 용접이나 단조 방식을 통해 작품의 표면을 변형시키는 방법은 작품 자체를 주목하게 하지만 가공을 최소화한 작품은 작품의 물리적인 외관과 작품이 놓일 실제 공간을 주목하게 한다. 작은 전시장의 삼각뿔 조각은 창밖 너머로 작품이 어떻게 보일지 상상하면서 계획했다고 한다. 일부러 창밖을 통해서는 작품의 전체를, 삼각뿔의 뾰족한 부분을 조망할 수 없도록 했다. 큰 전시장에서는 천장의 조명 레일의 간격을 고려하여 작품의 크기와 높이를 결정했다.

작품 밖의 (전시) 공간은 비어있는 상태에 불과하다는 의미로 ‘화이트 큐브 White Cube’라고 말한다. 최기석의 작품은 전시장의 크기와 모양 등 전시 공간의 물리적 조건을 반영하기 때문에 화이트 큐브의 신화를 깨버린다. 공간마저 작품을 구성하는 일부분이 되면 관람자가 주목해야 하는 것은 작품이 재현된 공간의 경험이다. 결국 조각의 이미지가 아닌 물질이다. 물질은 망막이 아닌 몸으로 경험되는 것이다. 관람자는 대형 조각이 놓인 좁은 전시장 공간을 불안하게 걸어가는 것과 작품과 밀착된 공간 안에서 철의 냄새를 맡고 붉게 변한 철의 색을 바라보고 거친 표면을 슬쩍 만져보는 경험마저 작품 감상의 일부로 편입시켜야 한다.

철은 공기에 부식되어 녹이 슬고 붉은색으로 변한 피부를 노골적으로 드러낸다. 최기석이 찾고자 한 것은 가공하지 않은, 있는 그대로에 바탕을 둔 아름다움이다. 그는 철이라는 물질을 자신이 인위적으로 변형시키거나 어떠한 형상을 연상시키려고 하지 않고 철의 성질을 존중하는 선에서 최소한의 개입만 스스로 허용했다. ‘가공하지 않는다’는 것이 그의 목적이 아닐 것이다. 꾸미지 않는다는 것, 억지로 관념이나 내용을 주입하지는 않는다는 것이 그의 목적이 아니었을까. 가공하지 않아도 철의 물리적 성질만으로 작업의 완전성을 갖는 것 말이다. 그래서 녹이 슨 표면은 자연에 풍화된 연약한 피부 같지만, 철의 단단하고 묵직한 무게감은 변함이 없다.

Modernist art in the 20th century raised the hand of freedom and subjectivity, alongside genre-based boundaries. Modernist sculptures disavowed the strict rules of what sculptures could present, as well as the elements of the fantastic. It thought regressive the embodiment of specific stories and themes within the sculpture. About a century past, how relevant are those modernist attitudes? Contemporary sculptures still appreciate the aspect of fine art, but they have also been part and parcel to blurring of boundaries between painting and sculpture, as well as between sculpture and architecture. Artists continue to imbue sculptures with intuition and emotive force, and the hands-on sentiment continues to be important. Kiseog Choi's iron sculptures are compared to the deeply weathered surface of field stones. Geometrical structures in sculptures evoke a visceral and emotive response from the spectator. With that in mind, Choi’s drawings on paper become a metaphor for the iron surface. Sculptures already give away too much, as it remains rational and neutral.

Kiseog Choi’s previous works explored iron surfaces by means of welding and planishing. This exploratory practice was his vehicle for 35 years. In his upcoming solo exhibition at GALLERY2, the artist presents iron more candidly than ever. He wanted to return iron to its original state, as it has been, before it has been treated or processed. It required the introduction of structure while avoiding any damage to the surface, and this meant only assembly was possible, and his usual welding and planishing could not be used.

This exhibition will also feature Choi’s first drawn works. Before each ironwork, Choi draws and plans the process, as if it were a blueprint. The simple compositions and indifferently blank spaces of the drawings resemble his iron works, but the spilling of colors and the black-white contrast hint of physical properties not found in the iron works. Choi shares that he hopes for the drawings to be ‘unaffected byproducts’. He goes over the paper numerous times with charcoal, iterating and crushing the black unto the material, faithfully imparting the weight and density of iron unto paper. Once colored, the surface evokes the texture of iron; not as an additional layer, but as material transformation of a sheet of paper into a sheet of iron. The drawing could not be more sculptor.

The exhibition hall is partitioned in two. One partition houses a trigonal pyramid that stands 360cm with a footprint dimension of 240cm on all sides. The other houses a rectangular sculpture with dimensions 240cm in depth, 480cm in width, and 360cm in height. The iron surface completely covers the spectator’s field of view with overwhelming scale. The size and form of the work reflects the physical conditions of the exhibition space. Transformation of the surface via casting and forging draws attention to the overall work, but minimal manipulation of the work draws attention to the external physicality and the actual space occupied by the work. In the small exhibition hall, the trigonal pyramid sculpture was planned while envisioning the view of the work through the outside window. Choi intentionally positioned the sculpture so the outside window view had the apex of the pyramid and its overall form obscured. In the large exhibition hall, the sculpture was planned with respect to the spacing of the ceiling lighting rail.

The space removed of the work is empty, referred to as white cube. Kiseog Choi’s sculptures are colloquial to the shape and size of the exhibition space, defying the very definition of indifference as implied by a white cube. When the space becomes part of the appreciative experience, the spectator must take in not only the artwork but the spatial experience where the work is represented. That is, not the image of sculpture but its substance. Substance has to be experienced at a visceral level, much deeper than the retina. Viscerality encompasses the uneasy circumambulation of the cramped exhibition space around the large sculptural work, the olfactory experience of the rusty iron, and even lightly placing fingers on the rough surface.

The corroded red iron is candid in its bare and lurid skin. Choi seeks raw, unadulterated, unfurnished beauty. He minimized any employment of artificial transformation or evocation of imagery. Any input was constrained to maximize fidelity of iron’s natural property. However, unprocessed was not his end goal; rather the avoidance of embellishments and forced impregnation of thoughts and feelings. There is plenum to material itself, irrespective of human interference. The rusted surface may appear worn and weathered by the great forces of nature, but gravity and fortitude remains unchanged; sufficient.