1248: 권세진 Sejin Kwon

갤러리2에서 권세진 개인전 <1248> 개최

2019년 5월 9일부터 6월 8일까지 평창동 갤러리2에서 권세진 개인전 <1248>이 개최된다. 한 장의 풍경 사진의 두 가지 방식의 그리드로 분할하여 수묵화로 그려낸 권세진은 먹의 관념적인 전통성에서 벗어나 그림을 위한 매체로써 탐구한다. 이번 전시에서는 동일한 수면의 이미지를 1200장의 화면으로 구성한 작품과 같은 이미지를 48점의 그림으로 작품이 선보일 예정이다.

풍경화를 감상할 때, 우리는 어떠한 지식도 필요 없다. 자연의 변화무쌍함과 웅장함, 화가의 필력과 섬세한 감수성. 이 모든 것은 누구나 알아볼 수 있다. 어쩌면 우리는 이것을 너무 당연한 것으로 여기고 있는지 모른다. 아름다운 그림 앞에 서는 순간, 이것이 그림이란 사실을 잊어버리거나 ‘그림’ 같은 풍경에 도취되기 때문이다. 그러나 풍경화는 화가가 본 것을 그대로 옮겨 놓지 못한다. 그저 자신이 선택한 매체를 통해 자연을 해석할 뿐이다.

권세진은 이번 개인전에서 바다의 풍경을 묘사했다. 이미지는 전적으로 사진에 의존했으며 오히려 먹과 농담의 운용을 즐겼다고 한다. 그는 사진이 (그림보다) 덜 형식화된 대상이라고 여긴다. 그러한 생각은 대상을 증거하고 박제하는 사진의 속성에 기인했을 것이다. 동양화의 전통적인 의미에서 사진을 보고 그린다는 것은 사실 어불성설이다.

서양의 풍경화는 수정이 용이한 유화물감을 이용해서 자연을 과학적인 원근법으로 표현한 그림이다. 동양의 산수화는 수정이 어려운 종이 위에 필과 묵으로 자연을 본 화가의 주체적 체험을 주관적 정취로 표현한 그림이다. 사실(寫實)성, 사의(寫意)성, 이상(理想)성이 종합을 이룬 그림이 바로 산수화다. 권세진은 자신이 찍은 여수의 바다를 그렸다. 이유는 바다 물결이, 그 물의 흐름과 자연의 질서가 먹과 필의 효과를 가장 잘 보여주기 때문이었다. 그림은 단지 그가 사용한 매체를 다시 관찰하도록 제안한다. 질문은 무엇을 그린 것인가가 아니라 어떻게 그린 것인가로 던져져야 한다.

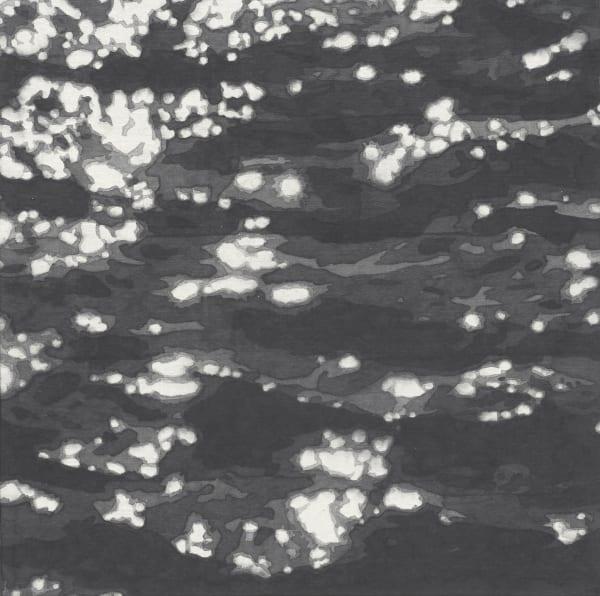

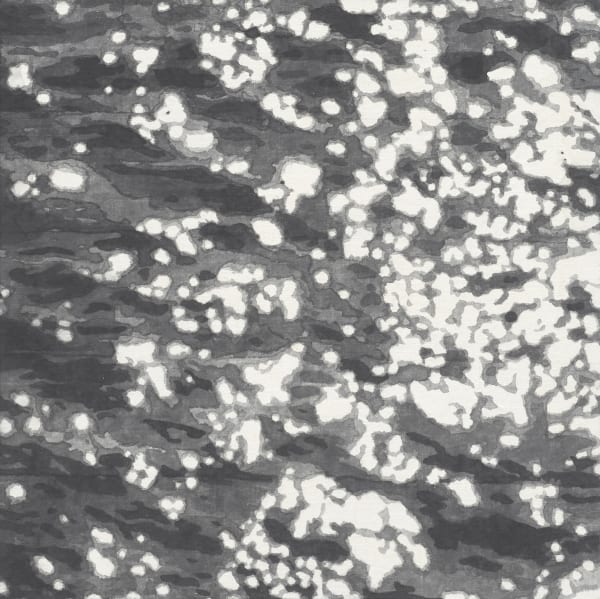

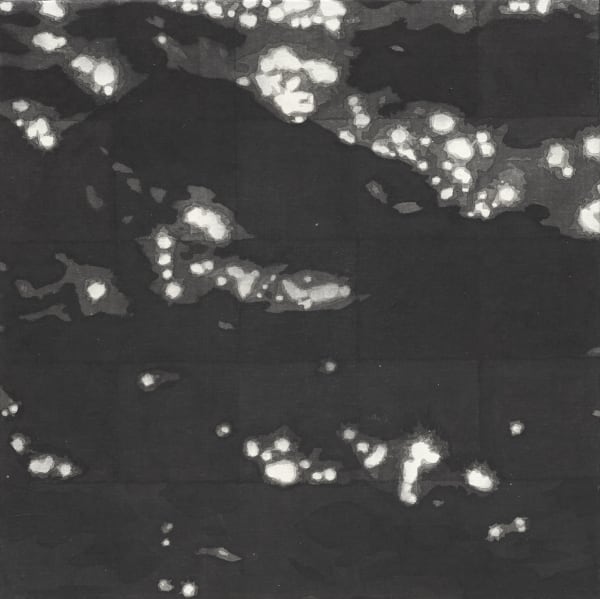

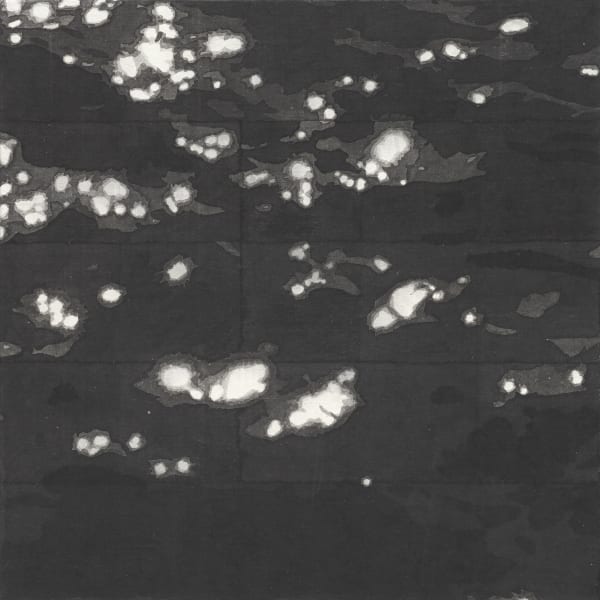

권세진은 먹의 농담(濃淡)만으로 그림을 완성했다. 화면에는 먹의 농(濃)과 담(淡)의 상호관계만 있을 뿐이다. 이를 가장 잘 보여주는 부분이 수면 위에 빛이 떨어지는 부분이다. 먹으로 그려진 부분과 그려지지 않은 부분은 마치 ‘켜짐’과 ‘꺼짐’, ‘예’와 ‘아니오’와 같이 극단적인 대비를 이루는 암호와 같다. 그의 그림에서 환영을 창조하는 것이 바로 빛을 선명하게 보여주는 먹의 상호관계다. 그 예기치 못했던 명도 대비 즉, 먹의 농담은 마치 그림 속에 빛이 흘러들어오고 있는 착각을 불러일으킨다.

먹의 오랜 전통성은 권세진에게 수묵화를 의도적으로 멀리하게 했었다. 사진을 보고 그리는 자신의 방식과 관념적인 그림의 주요 요체인 먹이 상충한다고 생각했기 때문이다. 수묵화는 지지체인 종이에서 먹이 마르기 전에 완성해야 한다. 먹의 번짐을 이용해서 붓질이 어울러 지도록 그려내야 가장 좋은 균형을 이룰 수 있기 때문이다. 이러한 먹의 성질이 눈앞의 자연이 아닌 관념적인 자연을 담아내는 산수화의 정신과 상응했던 것이다. 그는 수묵화를 중시하는 남종문인화 정신이나 먹을 귀하게 여기는 평담(平淡)사상에서 벗어나 먹을 그림의 매체로써 탐구하려는 태도에서 수묵화를 출발한다. 그래서 이번 신작은 먹에 대한 실험 결과와 같다.

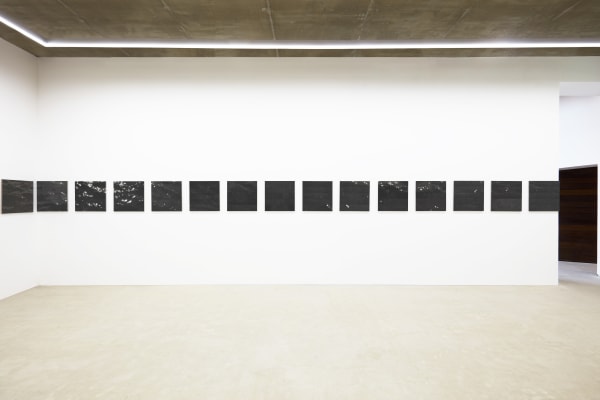

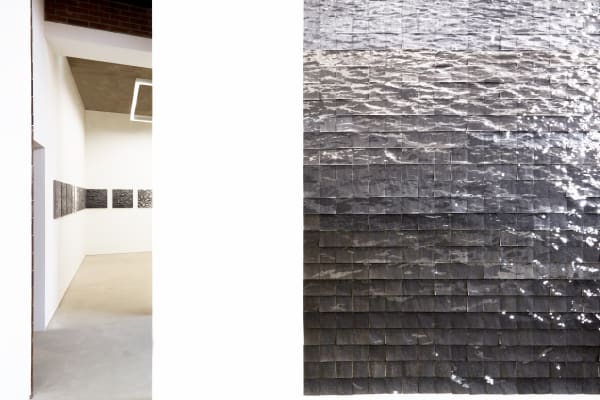

개인전 <1248>은 가로, 세로 10cm 크기의 1200개 화면이 1점을 이루는 <물의 표면>과 가로, 세로 50cm 크기의 48점 연작인 <바다의 단면>으로 구성되었다. 이것은 2점의 그림이라고 할 수 있고, 1200개로 이뤄진 1점과 48점의 그림이라고 할 수 있으며 또한 1248점의 그림이라고도 할 수 있다. 그리고 모두 한 장의 사진에서 출발했다. 동일한 이미지에 다른 규격의 그리드를 설정해서 1200개의 화면과 48개의 화면으로 나눈 것이다. 권세진은 두 가지의 그리드 방식을 통해 먹의 운용과 장면의 구성이라는 조형적 실험을 보여준다. 우리 눈앞에 놓인 실제 공간에 ‘그림’이 될만한 장면이 존재하는 것이 아니다. 화가가 공간을 이리저리 쪼개어 보는 동안 비로소 풍경화의 구성이 완성된다. 그러니 드넓은 바다를 부분적으로 담아낸 이미지도, 그것을 48개로 분할한 이미지도, 1200개로 분할한 이미지도 그림이 되지 못할 이유가 없다.

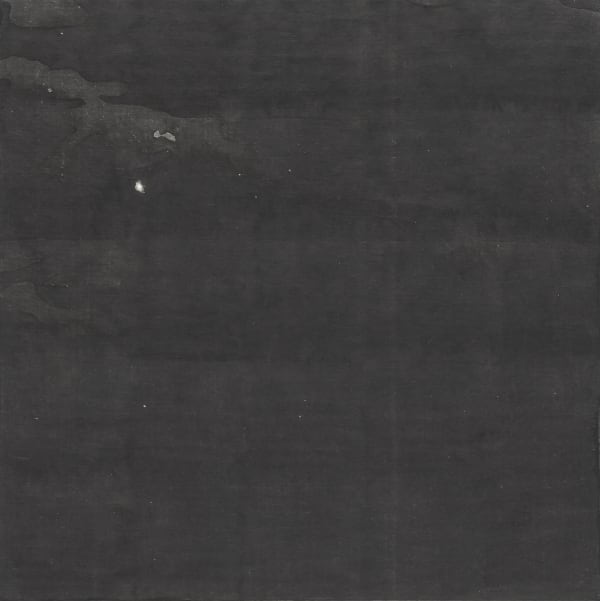

권세진은 하루의 작업량을 미리 정해서 규칙적으로 그림을 그렸다. <물의 표면>은 작가의 시간과 노동량을 보여준다. 그는 즉흥적으로 그리기보다는 되도록 오차가 없이 정해진 규칙 안에서 작업하려고 했고, 오히려 규칙 안에 존재하는 우연성을 즐겼다고 한다. 동일한 매체를 사용해도 화면마다 미세한 차이가 있을 수밖에 없다. 우연성은 매체의 속성과도 연관된다. 동양화는 먹을 붓에 침윤시키고 종이 위에 번지게 그리는 것이므로 우연성에 의존한다. 먹의 번짐을 인위로 이뤄내기는 쉽지 않다.

이번 전시에서 권세진은 그림의 형식, 매체를 체계화하고 싶었다고 한다. 실물을 증거하는 사진과 관념적인 매체인 먹을 접목하고 싶었던 것이다. 그의 그림은 전통적인 먹의 운용 방식과는 다른 방향성을 보여주면서 먹의 속성을 의식한 그림이다. 결국 그림은 그것을 이루는 재료에 의해 규정된다. 작가는 먹, 모필, 종이의 매체적 속성에 따라 그림을 완성한다. 먹의 액체성을 작가의 신체적 행위를 통해 종이 위에 안착시키는 것이 바로 그림이다. 물의 흐름, 매체의 순리를 따라야 하고 오직 그것만이 있을 수 있다.

Appreciating landscape painting is possible without any prior knowledge. Everything one needs to know is already contained in the frame; the grandeur and frivolousness of nature, the painter's capable strokes and sensibilities. They are there to be recognized. However, they are often forgotten and not appreciated. Standing before a beautiful painting, the viewer may forgo the recognition that it is a painting, or unknowingly become immersed with the picturesque landscape. Nonetheless, the artist may not encapsulate all that was beheld within a landscape painting. What he does is merely interpret nature with his choice of art material.

Artist Sejin Kwon's latest solo exhibition is an interpretation of ocean surface. More accurately, it is an interpretation of a single photo containing the ocean surface. A single photo was the only source he painted from. Kwon shares how enjoyable it was for him working with gradations of ink and chiaroscuro methods. He explains that photography is the less formal medium (in comparison to paintings). The explanation comes from the testimonial, or taxidermical nature of photographs. Oriental paintings by definition are paintings of imagined utopia, so painting in that style based on an actual photograph is oxymoronic.

The western world's better-known landscape paintings rely on perspective and oils to transpose nature onto the canvas. The oil is easily corrected then or later. The eastern world's landscape paintings are based on the artist's subjective interpretation of nature using brush and ink, which is very difficult to correct thereafter. Realistically detailed brushwork (寫實), abstractive freehand brushwork (寫意), and idealized visions (理想) are all present in the traditional oriental landscape painting (山水畵). The presented works are based on a photo of the ocean just off the coast of Yeosu, a port city located on the southern coast of the Korean Peninsula. The photo was taken by the artist himself. He chose the photo because nature's law and order was tangible in the slight undulating ocean currents; something that pairs well with the ink and brush. His presented work bodes the viewer to return to his choice of medium, and ask the question of how, rather than what?

Kwon painted using chiaroscuro methods as well as gradations(濃淡) between thick and thin. His use of this contrasting technique is clear in the dispersing column of glint down the top-center of his work. Like a binary code of on-off and yes-no, the areas painted and left blank becomes an area of material contrast. The illusion of trickling glint of light is presented by the contrasted shades of ink.

Kwon had consciously avoided the ink-and-wash style of sumukhwa (水墨畵). More specifically, he wanted to keep away from the history and tradition of style associated with the style. He painted from a concrete photograph, while the ink-and-wash sumukhwa was frequently the substrate for an elusive concept. Sumukhwa drawn on paper must be completed as a whole before the ink dries out. The deft brush must guide the propagation of the water and ink, to strike balance and wholeness before the ink dries. This temporal, fleeting character of working with ink-and-wash made it conceptually appropriate for painting the mountains and the trees as seen in one's mind. Kwon departed from the southern-school literati painting's (南宗文人畵) fixation on the ink-and-wash style, and the pyeongdam ideology's (平淡: even and mild, lucid) adulation of the ink. Instead, he explored the ink-and-wash as a medium, and in this exhibition is his sharing of what he found in that exploration.

Sejin Kwon's solo exhibition <1248> features two works. One is the quilted <Surface of the Water>, composed of 1200 smaller works each measuring 10cm by 10cm. The other is <Section of the Sea>, composed of 48 quilted pieces measuring 50cm by 50cm. The two may be understood as two separate works, 1248 works, or some variable thereof. However they are objectified, they are all based from a single photograph that was divided up into smaller portions using square blocks in a grid; one grid had 1200 squares while another had 48. The grids are Kwon's formative experimentations in the ink-and-wash style, on composition and technique. In the real world, there is no inherent scene or image to what the viewer beholds. That scene and composition is created as the artist works with a proverbial viewfinder. By extension of that logic, a partial view of the vast ocean, an even more partial one-forty-eighth, and one-twelve-hundredth images can just as well be images.

The artist set a regular amount to be painted each day and applied himself with diligence. <Surface of the Water> is a testimony to the countless hours of labor. He avoids impromptu applications working within precise predesignated boundaries. Any serendipity encountered was strictly within those set boundaries. Despite the highly iterative task and material, each panel has immutable variations. Such fortuity is inherent to the nature of the medium. Eastern paintings use a brush soaked in ink, drawn across the paper to allow for ink seepage and propagation. The final details are down to chance, and to control the propagation of ink is a difficult challenge.

For the present solo exhibition, Kwon wanted to provide structure to the style and medium of painting. He wanted to mesh photography as a testimony to reality and ink as a substrate of concept. He abandons the traditional goals of the style, but maintains an understanding of its properties. In the end, paintings are determined by their substrate. For this exhibition, the artist used ink sticks, a writing brush, and paper. The liquid state of ink transferred onto paper via the artist's performance is one definition of painting; a performance that demands an understanding of not only the nature of flowing water, but also an understanding of the nature of the medium at hand.