mite life: 이은새 Eunsae Lee

이은새 개인전, <mite life>에서 ‘mite’는 ‘진드기’라는 뜻도 있지만, ‘어린 것(가엽게 여겨지는 아이, 동물)’을 의미하기도 한다. 이번 전시에서 그는 개인적인 경험과 역사적 기록을 ‘물’이라는 공통된 사물로 접점을 만들거나 진드기(mite)에 대한 사소한 에피소드를 보여준다. 물과 진드기. 다소 거리감이 있는 두 대상은 우리가 일상적으로 마주하는, 그다지 대단할 것 없는 ‘사물’이라는 공통점을 갖는다. 그러니 ‘mite’는 진드기가 아니라 ‘가련하고 작은’ 대상이라는 점에 방점이 찍혀야 한다.

이번 전시는 작가의 사사로운 경험에서 출발했다. 술을 마시고 집에 들어간 날, 목이 말랐지만 물을 마시러 나가기 귀찮았던 순간에 언제 따 놓은 건지 알 수 없는 페트병을 발견하고 그 안에 든 물을 마셨다고 한다. 갈증은 해소됐지만 뭔가 찝찝한 마음에 마치 체한 것처럼 밤을 지낸 그는 원효대사의 해골물을 떠올리게 된다. 송대의 문헌인 『임간록(林間錄)』에 의하면 원효는 동료인 의상과 함께 당나라로 유학을 가다가 해골에 고인 썩은 물을 마시고 “모든 것은 마음에 달린 것”이라는 큰 깨달음을 얻는다. 작가는 원효의 이야기를 찾아보다가 더 흥미로운 설화를 발견한다. 의상이 낙산사에서 관음보살의 진신(眞身)을 만났다는 이야기를 듣고 그곳으로 향하던 원효는 냇가에서 빨래를 하던 여인에게 물을 달라고 청한다. 서답(당시의 생리대)을 빨고 있던 여인이 불그스름한 더러운 물을 떠 주자 원효는 물을 엎질러 버렸다. 하지만 이후에 그 물을 떠준 평범한 여인이 관음의 진신이었음을 깨닫게 된다.

원효설화에 등장하는 물은 큰 깨달음의 수단이나 신의 존재를 은유한다. 당연히 작가의 경험이 원효설화와 같지는 않다. 하지만 그는 물이라는 존재가 정서적인 변화, 생각의 전환, 어떤 차원이나 사고가 겹치게 되는 포탈(portal)같이 느껴졌다고 한다. 특별할 것 없는 사사로운 사물에서부터 변화가 시작된다는 점에서 작가의 경험과 원효설화가 접점을 보인다. 같은 공간과 시간에 그대로 존재하지만, 한 순간 입장이나 마음 상태가 변화하는 것. 즉, ‘물’은 하나의 매개체인 것이다. 여기서 작가는 물을 정지하여 움직이지 않는 정물(靜物) 그 자체 그리고 싶었다고 한다. 하지만 뭔가 미묘한 생각을 담은.

개인적인 경험, 자신의 실수, 평범한 일상에서 느낀 정서적 변화의 기점은 이미 작가가 오래전부터 회화로 재현했던 순간들이다. 그는 사소한 순간에서 촉발된 ‘이상한’ 지점과 경계에 주목했고 거기에 상상이 덧붙여졌다. 그 이상한 지점과 경계란 스스로 당연하게 생각했던 것이나 규칙적인 패턴을 뒤엎는 상황을 말한다. 자신의 그림은 스스로에게 하는 말 같다고 한다. 이미지가 너무 수수께끼 같아서 쉽게 알아볼 수는 없겠지만, 그의 그림은 메모하고 체크하면서 어떤 편협한 사고에 빠지거나 매몰되지 않게 뭔가를 상기 시켜주는 이미지이기 때문이다. 이번 신작에 다른 점이 있다면 상황이나 인물 묘사보다 사물을 더욱 집중해서 관찰했다는 것이다.

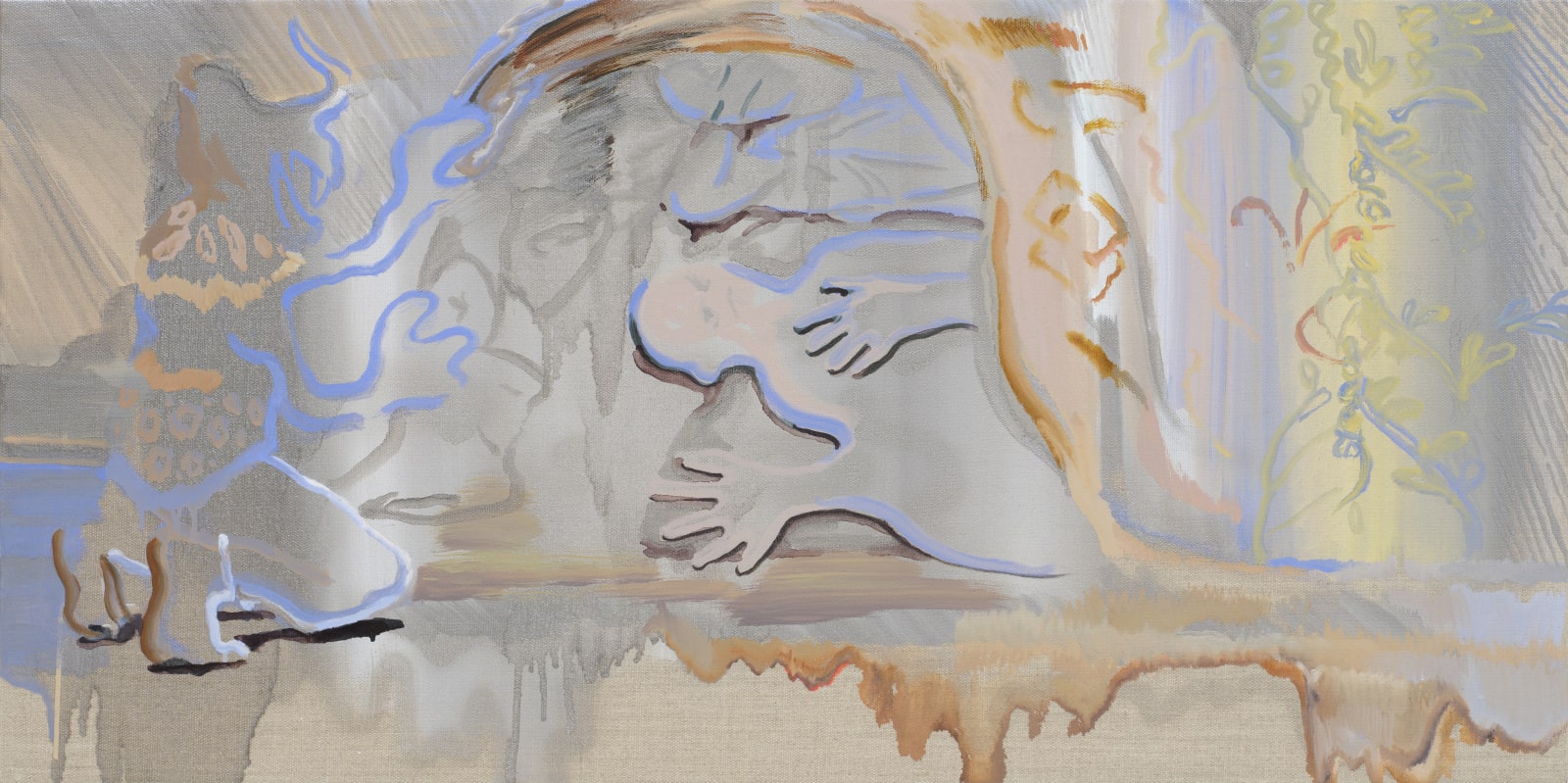

300호 크기의 <Mite life 1>은 원효대사의 해골물 설화와 작가의 경험이 뒤섞여 있다. 또 다른 300호 작품 <Mite life 2>에서는 17세기 네덜란드의 정물화인 바니타스(Vanitas)처럼 해골이 놓여 있다. 두 작품은 모두 해골이 등장하지만, 상황에 따라 원효대사의 해골과 바니타스의 해골로 다르게 읽힌다. 두 작품이 연관성은 없지만, 해골이라는 공통된 사물이 각 그림에서 다른 의미로 해석되는 차이점이 흥미롭다. <파인해골>에서 한 여성이 해골과 파인애플의 형상이 합쳐진 물건을 들고 있다. 기존의 일상적인 사진에 착시 현상처럼 합쳐진 이 이미지는 바니타스의 해골이나 원효설화의 해골 이야기를 상징하는 듯하면서도 두 이야기에서 모두 미끄러지듯 빠져나간다. <Mite life 4>, <튤립이 있는 정물화>와 같은 작품들은 치밀한 구도의 정물화가 아닌 재빠르게 순간적인 장면을 담아내는 스냅사진처럼 사물 혹은 사물이 놓인 상황을 담아낸다.

(이미 예상했겠지만) <mite life>라는 전시명은 정물화를 의미하는 ‘Still life(정물화)’를 조금 비틀어 낸 것이다. 정물화 중에서도 가장 유명한 것은 17세기 네덜란드의 바니타스 정물화일 것이다. 당시 유럽인들은 종교개혁이나 흑사병으로 인해 자신들이 이룩한 찬란한 문화와 문명이 순식간에 황폐해지고 일상생활이 파괴되는 순간을 경험하게 됐다. 이러한 경험이 예술에도 영향을 미치면서 물질세계에 대한 반성 및 죽음에 대한 성찰을 주제로 한 정물화가 대두된다. 이는 인간에게 익숙하고, 자연스럽고, 당연하다고 생각하는 것이 사실은 그렇지 않음을 정지된 사물을 통해 드러내는 것이다. 정교하고 사실적인 묘사의 바니타스와 다르게 이은새는 역사적 기록과 개인의 경험, 과거와 현재, 구상과 비구상이 뒤엉켜 낯설고 모호한 화면을 만들어 낸다. 반면 그는 정지된 사물이 발산하는 ‘무언가’를 보여주고 싶었다고 한다. 그것은 아마 익숙한 사물이 어느 순간 여러 상념과 상상 그리고 심정적 변화를 불러일으키며 편협한 사고를 전복시키는 힘을 말하는 것인지 모른다. 그런 면에서 그의 정물화는 바니타스의 형식보다 그 의미와 더 접점을 이룬다.

Eunsae Lee’s upcoming solo exhibition is titled mite Life. Here, mite may mean the arachnid pests, but also a small child or animal, especially when regarded as an object of sympathy. For mite Life, Lee presents points of connection between personal anecdotes and matters of historical record, across the subject of water and with minor episodes involving mites. Water and mites are seemingly unrelated things, but share an aspect of trivial mundanity, or just not very impressionable daily. That is to say, mites in this exhibition are not about the pests but the meek and insignificant deserving of sympathy.

This exhibition was conceived from a personal experience. Lee was parched, but also drowsy. So much so that she wished not to step any further than she must; she had returned from a night out drinking. Finding an open plastic bottle, she took a swig. She did not remember why the bottle was there or when it was opened. It hardly mattered. Once her thirst was quenched, she could not shake off the question of why that bottle was there. Was it food poisoning, or just an upset stomach? Was it all in her head? Uncomfortable thoughts raced through her mind all night. Coming back to her senses, she was struck by how much her experience resonated with that of Wonhyo (617-686 CE) the Buddhist philosopher. Imgallok (林間錄: Anecdotes from the Groves [of Chan]), written during China’s Song Dynasty, chronicles Wonhyo and his scholar-monk companion Uisang setting off to Tang China to study the Yogācāra teachings. The story goes that the pair are caught in a heavy downpour and forced to take shelter in what they believed to be an earthen sanctuary. During the night Wonhyo is overcome with thirst, and reaching out grasps a gourd and drinks; refreshed with a draught of cool, refreshing water. Upon waking the next morning, however, the companions discover that their shelter was in fact an ancient tomb littered with human skulls, and the vessel from which Wonhyo had drunk was a human skull full of brackish water. Eunsae Lee was researching more on this story when she found an even more amazing account of the two companions. Told that Uisang encountered the physical incarnate (眞身) of Bodhisattva Guanyin at Naksansa Temple, Wonhyo also heads to slopes of Naksan Mountain. On his way, he encounters a woman by the river, washing clothes. Thirsty from his long walk, Wonhyo asks the woman for water. The woman scoops up a fill of water from the river, but it is red with the sanitary napkins she had been laundering. Wonhyo is taken back, and spills the water. It was later that Wonhyo comes to realize that the woman was the physical incarnate of Bodhisattva Guanyin.

In the two tales of Wonhyo, water is a recurring metaphor. It serves as a means for enlightenment, a transcendent presence. Clearly, the artist’s experience were not literal reiterations of Wonhyo’s path to enlightenment, but she experienced water as a passage of emotional transformation, change in perspective, or even a realm of multitudinous dimensions or thought patterns. Both Lee and Wonhyo’s journey to change start from an object of seeming mundanity. Both experience water through change in the inner state, regardless of actual space and time. In that state, water is the medium, and the Lee wished to paint still life of water as a still medium that is completely unmoving, but with an aspect of subtleness.

Mites also brought about perceptual change, gradually showing up in her works as a point of interest. Certain trivial things tend to generate obsessive behavior once it enters the mind. The artist suffered an infestation of mites for some time and remembers struggling with an obsessive desire to be completely rid of them, to the point of developing a problematic anxiety. She wished that she could return to a point in time when she was not aware of their existence, but also, she knew that she was obsessing over something could be trivial. Paradoxically, the impact of trivial things can be more unsettling and shocking. Both water and mites shared that sense of triviality amplified into something far greater in effect and experience.

Anecdotes, mishaps, and even the mundane experiences that caused a shift in the artist’s inner person have long been the moments that Lee has tried to capture on canvas. Those subversive and uncanny moments captured her interest, and she extrapolated upon them, and took them further in her imagination. The artist likens her paintings to a soliloquy. Like self-utterance, her works are often enigmatic and not immediately decipherable, but they also work to check and balance her practice from falling into some narrow corridor or branch. If there is one thing that her latest exhibition brings to her practice is a shift to objects rather than situations or characters.

The No.300 canvas size (290cm wide) of <Mite life 1> is a mingling of Wonhyo’s skull-water experience and the artist’s own unfortunate swig. The other No.300 canvas work <Mite life 2> shows a skull placed like a 17th-century Dutch still life Vanitas. Both works feature skeletons, but context defines which is that of Wonhyo or of Vanitas. The two are unrelated, but the shared skull-object in each are interpreted variably. In <Pine-skull>, a female figure holds an object that appears to be something of a skull and a pineapple. Like an optical illusion of mundane objects, they possibly are loose and illusive allusions to Vanitas or Wonhyo. Works such as <Mite life 4> and <Still life with Tulips> are not still-lifes with intentional compositions. Rather, they are fleeting snapshots that quickly capture moments of objects and situations before they continue on their effervescence.

By now, exhibition title mite Life may have given away its spin on still-life. 17th-century Dutch Vanitas still-life paintings are arguably the most widely known in the genre. That century was when Europeans underwent the Reformation and the Black Death; instantly subverting and even destroying a significant portion of their splendid culture and civilization. The experience of those events impacted art, and still-life paintings came to the forefront with themes reflecting upon materiality and upon death and what lies beyond. To human beings, some things are familiar, only natural, and taken for granted, but still-life reveals that it is not actually so. The delicately realistic depictions of Vanitas are not in Lee’s intertwining of historical events and personal anecdotes, past and present, figurative and non-figurative composition on the ultimately ambiguous and unfamiliar canvas. What is on canvas is the artist’s desire to present a stationary object that exudes some thing. Perhaps it is the thing that subverts the expectation placed on familiar objects; the thing that changes the inner self. And through this subversion, Lee’s still works pay homage to the function and meaning of the Vanitas; not its format.