겨울 Winter: 김종학 Chonghak Kim

김종학의 겨울展

눈(雪)의 산

심은록 (SimEunlog MetaLab 연구원 및 미술비평가)

“국경의 긴 터널을 빠져나오자 눈의 고장이었다.”- 가와바타 야스나리, 『설국』에서

Winter, oil on canvas, 200x780cm, 2020

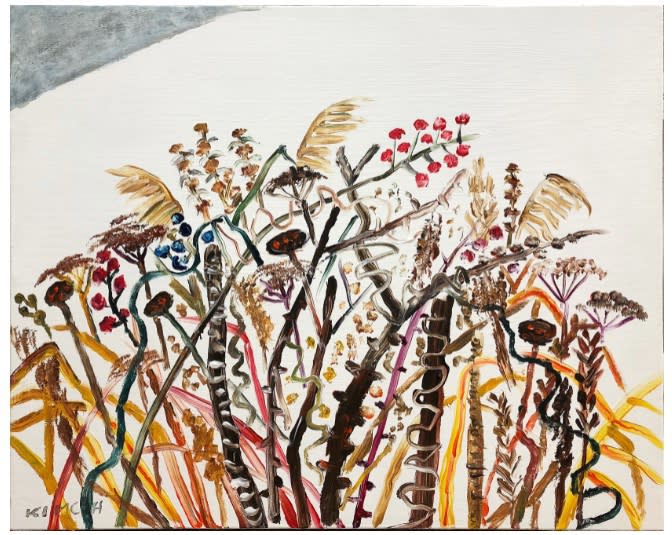

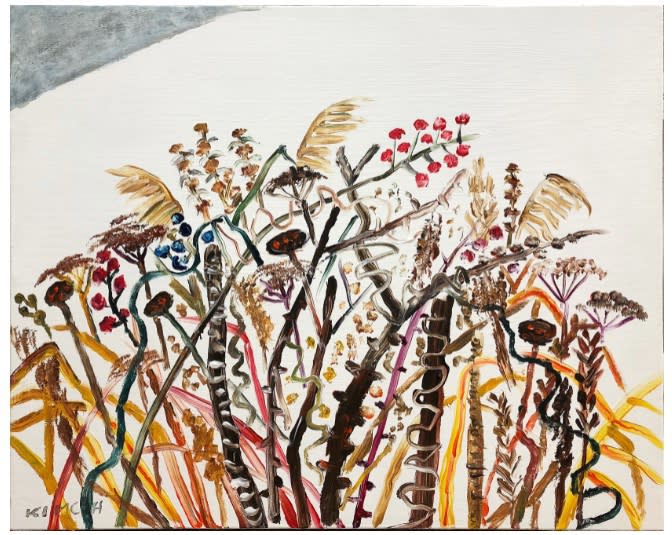

김종학의 여러 별명가운데는 ‘설악산 화가’도 있다. 35년간 설악산에 머물렀고, 그곳의 꽃, 초목, 풍경이 그의 주요 소재이기 때문이다. 그는 겨울풍경을 좋아하는데, ‘설악산’(雪嶽山)이라는 명칭도 겨울에서 출발한다. 『동국여지승람(東國輿地勝覽)』에 의하면, 한가위 즈음부터 눈이 쌓이기 시작하여, 하지가 되어야 녹기 때문에 ‘설악’이라고 불렀다. 『증보문헌비고(增補文獻備考)』에서도 산마루에는 오랫동안 눈이 남아있고, 암석도 눈처럼 하얗기에 설악이라고 했다. 이러한 설악이 물씬 묻어나는 김종학의 겨울은 사계 중에 가장 색다르다. <Winter, 2020>에서는 온 세상이 눈으로 덮였고 세속(性)과는 다른 성(聖)스럽기까지 한 세상이 펼쳐진다. 겨울마다 보아도 매번 신비로운 설경, 사람의 흔적이 닿지않은 순결하고 순수한 눈의 세계와 그때 느낀 작가의 숭고한 감정도 엿보인다. 성(聖)스러운 세계라고 해서 행복과 평안만 있는 것은 아니다. 매서운 바람과 눈의 무게로 허리가 꺾이거나 휘어 버린 초목들이 보인다[1]. 평상시 매정하게 여겨진 가시나무의 붉은 기운이 오히려 따스하다. 도시에 사는 현대인들에게는 점점 더 생소해지는 풍경이다. 『설국』의 첫 문장처럼, 길고 긴 터널을 지나야만 볼 수 있는 아련한 기억 같다. 그저 하얀 것만 같은 눈의 나라가, 작가의 감성으로는 얼마나 다양할 수 있는지 갤러리2의 <겨울>전에서 펼쳐진다.

Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm, 2017

Winter, oil on canvas, 65.4x91cm, 2002

봄, 여름, 가을의 숲은 여린 초목의 생명의 발아, 터져 나오듯 분출되는 젊은 녹음, 혼미할 정도로 화려한 단풍 등에 시선이 빼앗겨 산이 드러나지 않는다. 반면에 겨울에는 잎을 떨구는 앙상한 나무 사이로 산이 서서히 모습을 드러낸다. 이번 전시에 포함되지는 않았지만, 설악산 전체 풍모와 성격이 한 눈에 드러나는 원경을 화폭에 담는 것도 주로 겨울이다. 또한 겨울은 그조차 잊고 있었던 고향 신의주 기질이 드러나기도 한다. 상기 두 작업 <Untitled, 2017>과 <Winter 2002>는 산이 앞 뒤로 겹쳐 있는 풍경이다. 기하학적 추상으로 보이는 이 작품들은 자연이 주는 추상이지만, 설산에서 흔히 보이는 정경이기도 하다. 작가가 늘 말하듯 자연에는 추상과 구상이 함께 존재한다. 김종학의 작업에 대한 선이해 없이 <Untitled, 2017>을 처음 보는 관람자라면, 독특한 기하학적 추상이라고만 여길 수도 있다. 산에 내린 눈은 원근감과 볼륨감을 눈아래로 감춰버리곤 한다. 그나마 나무가 근경에서 원경으로 갈수록 조금씩 작아지기에 다소나마 거리감을 느낄 수 있다. 산등성을 따라 머리에 눈을 소복히 쌓은 나무들이 이어지며 공교롭게도 y자 선[2]이 그려졌다. <Winter 2002>에서 전경의 나무는 색깔과 형태를 알아볼 수 있을 정도로 제법 또렷해서 금방 산(山)임을 알 수 있다. 또한 나무들이 원경으로 갈수록 급격히 작아지기에, 원근법과 볼륨감이 함께 느껴진다. 뒷편 산이 파란 그늘로 덮혀있어 한층 깊숙한 거리감을 준다. 산등성이를 따라 나무들이 섬세하게 표현되었다. 맑고 따스한 날씨 덕분에 나무들은 머리 위의 하얀 눈을 대지에 내려 놓았기에 투명한 겨울 공기와 나뭇가지가 섞여서 y자가 그려졌다.

흔적. 현존과 부재사이

Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm(each), 2017

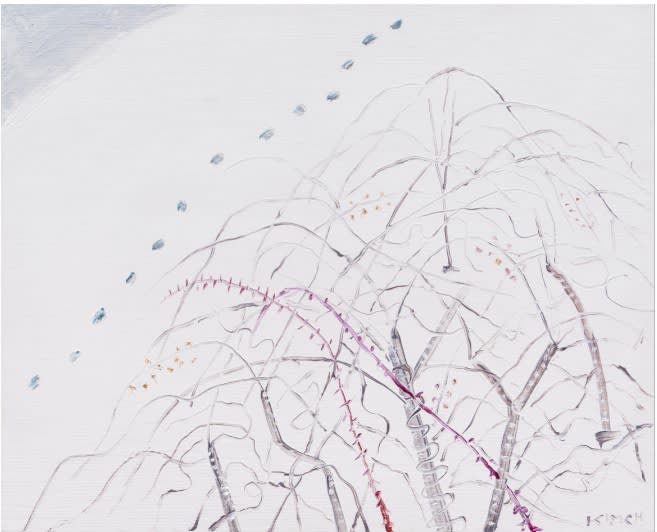

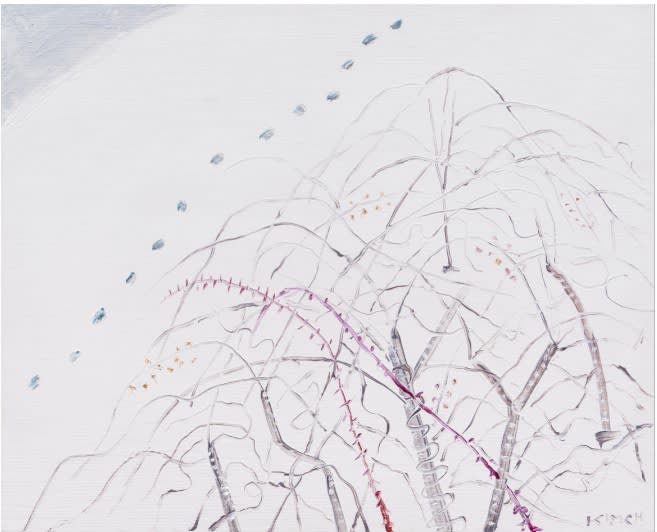

상기 <Untitled, 2017> 네 점을 비롯하여, 김종학의 설경에는 눈이 온 뒤 아무런 흔적(특히, 발자국)도 없이 순결하고 순수한 눈의 세계가 화폭에 담기곤 한다. 마치 예술의 성스러운 이상향 같다. 설악산 스튜디오의 현판이나 좌우명처럼, 그가 직접 쓴 ‘無垢(무구)’라는 글도 함께 떠오른다.

[좌로부터 1, 2, 3, 4]

[1]~[4] Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm(each), 2017

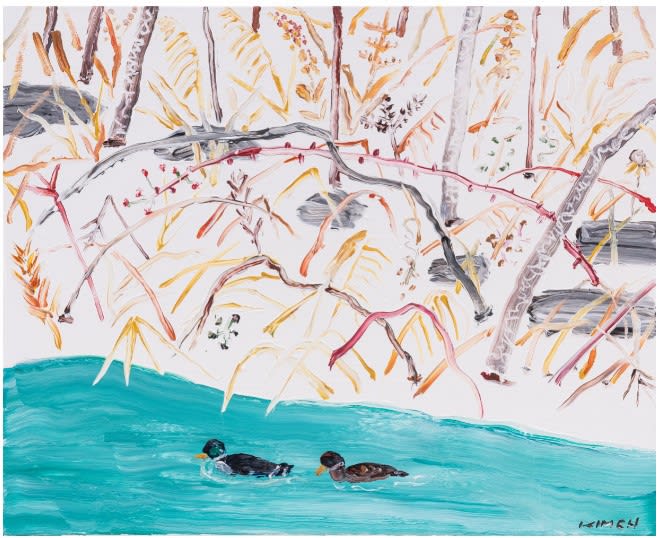

작가의 작품 가운데는 [1]<Untitled, 2017>처럼 대담하게 발자국이 찍힌 것도 있지만 대부분의 경우 조심스럽게 흔적이 남는다. 이 발자국들은 주변 공간이 하얗게 눈으로 덮여 있다는 사실을 관람객에게 상기시키는 듯 하다. 전경이나 원경에 있는 수목의 자유로운 리듬을 쫓다가 하얀 공간에 관심을 갖지 않을 수도 있는데, 이를 다잡아 불러일으키는 것이 발자국이다. 마치, 이우환의 <대화>연작에서 네모난 붓의 흔적들이 주변의 공간을 울리게 하는 것과 같은 맥락이다.

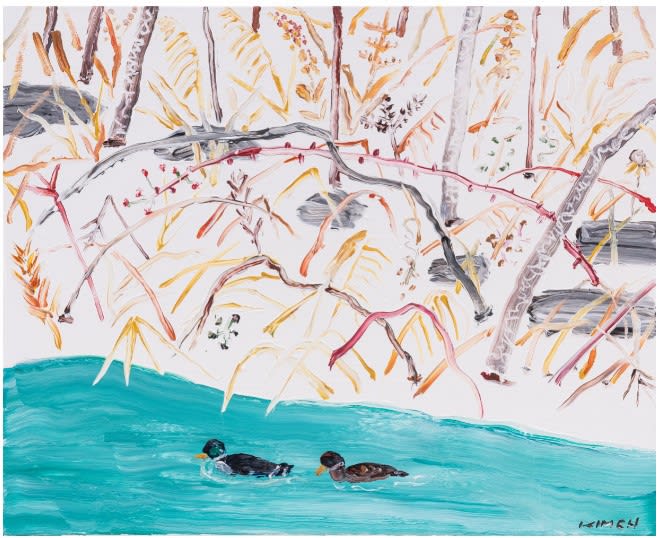

김종학의 [2]<Untitled, 2017>에서 발자국은 화면 오른쪽 끝에서 시작하여 하천을 따라 가다가, 화면의 반에 이르기도 전에 사라진다. 발자국의 주인은 오리가 아닐까? <Untitled, 2017>에서처럼 한 쌍의 오리가 유유자적 헤엄치고 있는 모습이 종종 보이기 때문이다. 하천으로 들어간 오리는 헤엄을 쳐서 화면 밖으로 나갔거나, 그 반대로 하천에서 나와서 화면 오른쪽으로 사라진 것일 수도 있다. 자연의 신비는 끝이 없다. 한 몸에 두 개의 다른 체온[3]을 지닌 오리는 뒤뚱거림 아래 신비를 감췄다. [3]<Untitled, 2017>의 경우에는 발자국의 크기로 보아 흔적이 왼쪽 상단에서 시작하여 오른쪽 상단으로 올라가며 사라진다. 일렬로 찍힌 발자국으로 보아 사람의 것 같지는 않다. 또한 새의 발자국이라고 하기에는 크다. 어떤 동물의 흔적일까? [4]<Untitled, 2017>에서는 사람의 발자국같다. 한 줄이 아니라 나란히 두 줄로 남겨졌기 때문이다. 누구의 발자국이던 이는 살아있는 생명체의 흔적(trace)이다. 굳은 땅에는 발자국을 남길 수 없듯이, 생명의 흔적이기에 울림을 준다. 흔적은 자크 데리다에 의하면 “존재(현존)와 부재 사이의 결정불가능성”이다. 또한 김종학에게 있어서는 聖(무구)과 性(세속) 사이의 경계이기도 하다.

色澤無施(색택무시)의 이유

Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm, 2017

Moon, acrylic on canvas, 181.7x291cm, 2012

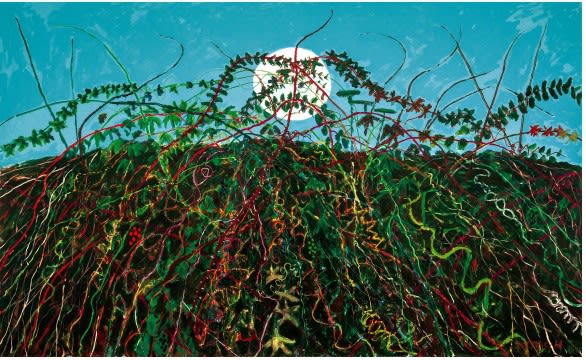

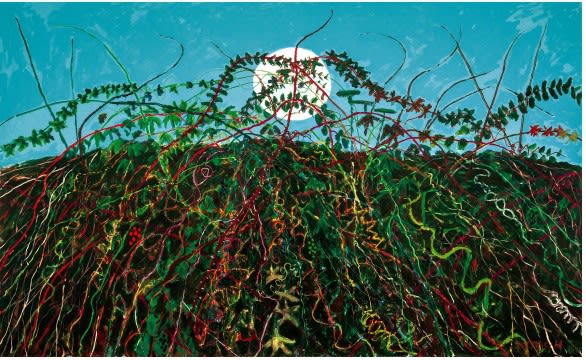

<Untitled, 2017>은 <Moon, 2012>의 겨울 버전 같다. <Untitled, 2017>에서는 배경, 색, 구체성은 사라지고 발광체를 향해 올라가는 기운만 남아있다. 이 작업을 보면 능호관(凌壺觀) 이인상(李麟祥)이 "색택(色澤)을 베풀지 않았거늘, 감히 게을러서가 아니라 심회(心會)가 중요해서"[4]라고 한 <구룡폭九龍瀑>의 제화(題畵)가 떠오른다. 이러한 연상은 김종학이 워낙 능호관을 좋아하여 매 인터뷰마다 언급한 덕분이다. 또한 그가 극찬하는 능호관의 <설송도> 구도가 김종학이 초목을 그릴 때 종종 보여지면서 연상되기도 했다[이 글의 ‘각주1’ 참조]. <Untitled, 2017>의 정취는 <설송도>보다 <구룡폭>에 가깝다. 자코메티가 인물에서 모든 기름기를 뺐다면, 이인상과 김종학은 풍경에서 모든 기름기를 뺀 것 같다. 이인상의 용어로는 ‘骨’이, 김종학의 용어로는 ‘氣’만 남았다. 김종학이 봄에서 가을까지는 ‘살’과 ‘색’에 무게중심을 두었다면, 겨울에는 ‘골’을 제시하며 오리처럼 자연과 예술의 다른 두 온도를 체감하게한다.

[1] < Winter, 2020>를 비롯한 김종학의 많은 ‘설경’에는, 그가 감탄해 마지 않는 이인상의 <설송도(雪松圖)>에 나오는 타지법(拖枝法: 90도로 꺾인 나뭇가지를 그리는 기법)이나, <송하관폭도>에 거의 눕듯이 기울어진 낙락장송의 구도가 보이곤 한다.

[2] Y자는 고대 유럽에서는 두 갈래의 다른 길인 聖과 性(세속), 지(知)와 열정, 등을 상징했다.

[3] 오리는 발목에 열교환기[원더 네트Wondernet 혹은 기(괴)망rete mirabile]를 장착하고 있다.

[4] 능호관이 직접 쓴 <구룡폭>의 제화(題畵)에서, 상기 내용과 관련된 문장은 다음과 같다.

“寫骨而不寫肉(사골이불사육) 뼈대만 그리고 살은 그리지 않았다.

色澤無施(색택무시) 색택을 드러내지 않은 것은

非敢慢也(비감만야) 일부러 거칠게 하려는 것이 아니다.

在心會(재심회) 마음에 깨달음이 있어서다.”

Kim Chong Hak, Winter exhibition

The Mountain Beneath the Snow

Sim Eunlog (SimEunlog MetaLab Researcher and Art Critic)

The train came out of the long tunnel into the snow country. The earth lay white under the night sky.

- Kawabata Yasunari, 『Snow Country』

Winter, oil on canvas, 200x780cm, 2020

Kim Chong Hak has numerous nicknames, and Seoraksan Hwaga (Seoraksan Mountain painter) is one of them. He lived at the foot of Seoraksan Mountain for 35 years, and the artist finds joy in painting the wildflowers, greenery, and landscapes he encountered there. He is also admired winterscapes, and the name Seoraksan (雪嶽山, great mountain of snowy peaks) is also based on the idea of winter. Dongguk Yeoji Seungnam (東國輿地勝覽, The Complete Conspectus of the Territory of the Eastern Country, 1481) describes the mountain gradually clothing itself in white, starting around Hangawi (a major mid-autumn harvest festival on the 15th day of the 8th month of the lunar calendar, or tr: around late September on the Western calendar), the snowline barely receding until Haji (Summer equinox, mid-June), earning it the seorak (snowy peak) prefix to san (mountain). JeungboMunheonBigo (增補文獻備考, Expanded Reference Compilation of Documents, an encyclopedia for culture and institutions published in 1908) also notes that snow persisted on the ridge, and the surface of the rocky mountain were also white like snow, hence the name seorak-san. Rich with the ambiance of snowy peaks, Kim Chong Hak’s Winter is the most unusual of his four season-themed quadrilogy. The earth lays pure under the sky in Winter (2020), pristine and sacred with negative space, elevated above any secular impurity. There is something hallowed about snowscapes, regardless of how many winters or how much snowfall one has witnessed. The artist recognized the blithe and the careless, untouched, and pure, a sublimity that he is no stranger to. Sacred and above secular impurity does not mean only happiness and peace. Unrelenting wind and heavy snow bend and break what grows out from the ground[1]. The scarlet thorn brush would have been a harsh sight, but it is rather warm in these paintings. These are sights that are increasingly unfamiliar for city dwellers. Much like the first sentence of 『Snow Country』, we must now pass through a “long tunnel into the snow country” to appreciate this somnolent view. A snow country so white, its many underlying timbre captured by the masterful brush of Kim Chong Hak, is presented in his solo exhibition Winter, at Gallery 2.

Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm, 2017

Winter, oil on canvas, 65.4x91cm, 2002

Kim’s forests of spring, summer, and autumn put the greens and life in the foreground. The sprouts, the gushing-forth of verdant energy, and the mesmerizing leaves of autumn obfuscate the mountain on which it is all happening. Kim’s forests of winter reveal this mountain, emerging forth from the tree, shedding their leaves and baring their branches. Although it is not part of his latest exhibition, Kim’s works that capture the full majestic character of Seoraksan Mountain are also in the winter. Winter also brings forth latent memories of Sinuiju - his hometown - and its visual similarities to the canvas. Untitled (2017) and Winter (2002) are mountainscapes with overlap in the front and back. The lines appear to be geometric abstracts - or abstractions from nature, but such sights are common on mountain paths during the winter. Kim always says that nature embodies both abstraction and figuration. His works may also seem to be mere abstraction and figuration to those who are unfamiliar with his paintings. Like linen over furniture, snow can obscure the sense of perspective or volume in mountains. Trees give some hint to the perspective, as they are drawn smaller in the distance. The snow frosted mountain ridge overlaps into a Y-shaped line[2]. The foreground trees in Winter (2002) are painted with enough clarity of line and distinction of colors that the background is quickly understood to be a mountain. Further into the background, the trees shrink, and the cumulative effective is of clear volume and perspective. The background mountain is also overshadowed in blue, adding a sense of depth and distance. The trees along the ridge have been painted with detail and texture. Thanks to the clear winter sky, the trees shrugged off the snow, creating a Y-shaped line of crisp winter ambiance and branches. The letter Y has long been prototypal of divergent paths between what is sacred and secular, what is known and unknown, intellect and passion, and so on.

Vestige. Between presence and absence

Untitled (2017), acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm (ea.)

Including the four paintings of Untitled (2017), Kim Chong Hak’s snowscapes are often without trace of any passage. They are pristine and pure. They are like the sacred Shangri-La of art. On a plaque in Kim’s Seoraksan Studio reads the two characters “無垢” (mugu, unspoiled) that he wrote himself.

[1, 2, 3, 4 from left to right]

[1]-[4] Untitled (2017), acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm (ea.)

Some of the artist's works are boldly footprinted like [1] Untitled (2017), but most are not so bold in their vestige. Oxymoronically, the footprints are a reminder of how white and how covered the mountain is. The gaze may be too busy following the larky rhythm of the trees in the foreground and the background. The footprints serve as focal points for the gaze to latch on and recognize the whiteness of it all. Lee Ufan's Dialogue series of paintings use vestiges of square brushes to create a resonant effect in the surrounding space.

Kim Chong Hak’s [2] Untitled (2017) footprints strut in at the far right of the screen, follow the stream, then trace off even before they cross the midline. Were these prints left by a duck? Untitled (2017) in fact, has a pair of ducks swimming leisurely. A duck may have waddled into the stream and sawm off screen, or into the stream on one side, and out the other. The mysteries of nature are boundless. A body with two different temperatures, the duck’s waddle[3] hides a curious mystery. [3] Untitled (2017) shows more footprints, from the upper left edge of the panel moving and disappearing into the upper right edge of the panel. Judging from the linear gait, it could not be a person. It is also too large to be a bird. What animal could it be? [4] Untitled (2017) footprints are likely human, as they run parallel. Whoever or whatever they were, these were living creatures capable of leaving a trace. Just as dry and barren ground accept no footprints, these resonate as traces of life. This is the profusion of “traces”, resulting from the disruption of presence and interplay of presence and absence, as Derrida had argued. For Kim, this is also the trace boundary between the unspoiled mugu and the secularized compromise.

Reasons for choosing dull colors without sheen (色澤無施)

Untitled (2017), acrylic on canvas, 53x65.1cm

Moon (2012), acrylic on canvas, 181.7x291cm

Untitled (2017) is arguably the winter version of Moon (2012). Untitled (2017) is devoid of background, color, and concreteness. Only the rising aura towards the source of illumination remains. Neung Ho Kwan (凌壺觀, penname of literti painter Yi Insang, 1710-1760) once explained a similar choice in the verses (題畵, painting with poetry) accompanying his Guryongpok (九龍瀑, Nine Dragon Waterfall) painting, “I did not give it the sheen of color, not for I had dared to be lazy, but to gather my mind”[4]. This association is by the artist’s well-documented fondness Neung Ho Kwan, having mentioned him frequently at interviews. Kim’s adoration for Neung Ho Kwang’s Seolsongdo (雪松圖, Painting of Pine Trees in Snow) appears in certain figurations of Kim’s plant-and-tree compositions.{ut}[refer to the first footnote of this text]. The emotional ambiance of Untitled (2017) is closer to Guryongpok (九龍瀑, Nine Dragon Waterfall) than to Seolsongdo (雪松圖, Painting of Pine Trees in Snow). In the way that fat was trimmed from Alberto Giacometti’s figures, Yi Insang and Kim Chonghak painted landscapes trimmed of all fat. By Yi’s expression, only the bare bones (骨) remain, and by Kim’s description only the essence of the energy (氣) remain. Kim’s works from spring, summer, and autumn focused on the cardinal and the color, and his works from winter present the underlying bones, conveying the dissimilar temperature between nature and culture (art).

[1] Winter (2020) and many of Kim Chong Hak’s snowscapes show aspects of tajiboep (拖枝法, a technique for drawing branches bent at right angles) as seen in Seolsongdo (雪松圖, Painting of Pine Trees in Snow) by Yi Insang who Kim admires; and in the style of nakrangjangsong (落落長松, grand old pine tree) reclining like Yi’s Songhagwanpokdo (松下觀瀑圖, painting of reclining pine before a waterfall).

[2] The letter Y has long been prototypal of divergent paths between what is sacred and secular, what is known and unknown, intellect and passion, and so on.

[3] Ducks are equipped with a countercurrent heat exchange system in their feet.

[4] Written by Neung Ho Kwan himself, the poetic verses accompanying his Guryongpok (九龍瀑, Nine Dragon Waterfall) painting are relevant to the above discussion:

“The bare bones were drawn and not the flesh (寫骨而不寫肉)s

The reason the sheen of colors were not revealed (色澤無施)

was not to willfully add distress (非敢慢也)

It was because I understand what was implied (在心會)”