Episode II : Home and Away: MATT CAREY-WILLIAMS x GALLERY2

EPISODE II: HOME AND AWAY,

CONTEMPORARY FIGURATIVE PAINTING IN BRITAIN

I: 과거와 현재

영국 회화의 명색부[highlight reel]는 구상의 어휘를 중심으로 이어져왔다. 반 다이크[van Dyck], 게인스버러[Gainsborough], 레이놀즈[Reynolds]의 비단결 같은 붓놀림에서 무어[Moore]와 스펜서[Spencer]의 독특한 질감, 런던화파[School of London] 대표 작가들이 쏟아낸 어두운 고동, 그리고 호크니[Hockney]와 샤빌[Saville]의 쿨하게 에로틱하고 단순한 듯 풍자적인 박자감에 이르는 다양한 작가들의 계보다. 이들은 화가로서 핵심적이고 성공적인 순간, 인간상을 물리적 형태 이상의 무언가로 승화시켰고, 다양한 지위의 지류에 기반한 일련의 관심사가 담긴 ‘몸’은 특정 계급이나 정체성을 상징하는 매개체가 되었다. 욕망의 특정 패턴과 패러다임, 그리고 끊임없이 변화하는 존재와 생성의 지경이 된 것이다.

이들은 대부분 런던에서 활동을 시작했고 또 지속적으로 런던을 기반으로 활동했지만 또 태생이 런던이거나 영국인이었던 작가는 드물었다. 반 다이크는 벨기에의 앤트워프 출신이었고, 프랜시스 베이컨[Francis Bacon]은 더블린 태생이었다. 루시안 프로이트[Lucian Freud]와 프랭크 아우어바흐[Fran Auerbach]는 베를린 태생이고 호크니는 무어와 마찬가지로 잉글랜드 북부 요크셔[Yorkshire] 출신이었다. 다시 말해 영국 구상 회화의 성공은 켄싱턴, 캠든, 왕립예술대학, 왕립예술원 등 런던의 예술 명소에서 꽃을 피웠으나 그 씨가 발아한 곳은 서퍽[Suffolk]이나 데번[Devon]같은 전원적 변두리에서였다.

전시제목 'Home and Away[고향, 먼 곳]'는 이러한 역사 속에서 드러나는 부조화와 반전, 여정과 모순, 근원과 기념을 포용하는 에피소드로, 전시 작품과 작가들의 주제나 분위기, 디자인은 쉽게 한 마디로 요약되지 않는다. 14인의 작가가 런던에서 활동하며 작가로 성숙하고 현재 집이라 일컫지만 전시는 서울의 ‘갤러리2’와 런던의 ‘매트 캐리-윌리엄스[Matt Carey-Williams]’에 걸쳐 두 개의 전시 장소에서 개최된다. 큐레이터이자 작가인 본인에게 이 전시는 물리적으로 분리되어 있지만 감정적으로나 직업적으로 연결된, 집과 타지 사이의 공간에 자리 잡고 있다. 이번 전시 작가들은 오늘날 영국 미술을 이룬 세대처럼 런던과 영국 밖에서 태어났지만 그들의 전시작은 영국 구상 회화를 향한 새로운 관심과 탐구심을 내포한다. 이탈리아와 가나 부모에게서 태어난 작가, 독일과 코스타리카 부모에게서 태어난 작가, 레바논 출신 작가들은 체스터[Chester], 콜체스터[Colchester], 뉴캐슬[Newcastle], 그리고 심지어 런던에서 태어난 작가들과 함께 오늘날 브리튼에서 산다는 의미, 그 경험의 총체를 그려낸다. 이렇게 전시는 상반되는 것과 일치하는 것의 복합체로서 기능하며, 수천 마일 떨어져야만 보이는 실천과 정치의 뒤섞임, 그리고 열정, 존재, 항쟁의 합창을 불러낸다.

II: 중심부과 주변부

이 에세이를 쓰고 있는 지금, 영국의 일부 지역이 불타고 있다. 극우 단체원들이 주도한 폭동으로 현재까지 전국에서 수백 명이 체포되었다. 가장 충격적이고 믿기 힘든 장면 중 하나는 로더럼[Rotherham]과 탐워스[Tamworth] 폭력배들이 망명자 보호시설을 불태운 것이었다. 광기에 찬 폭도들이 단순히 자신과 다르다는 이유만으로 겁에 질린 난민 가족들의 숙소에 연기를 지펴 넣어 뛰쳐나오게 하고 공격하려 든 것이다. 예이츠의 시구처럼 중심이 더 견디지 못할 때, 주변부에 있는 이들은 가장 극적인 논리, 이성, 배려의 전복을 경험하게 된다. 'Home and Away' 전시의 많은 작품들은 경험적, 지적, 정치적, 인종적 주변부의 불안과 동요를 다룬다.

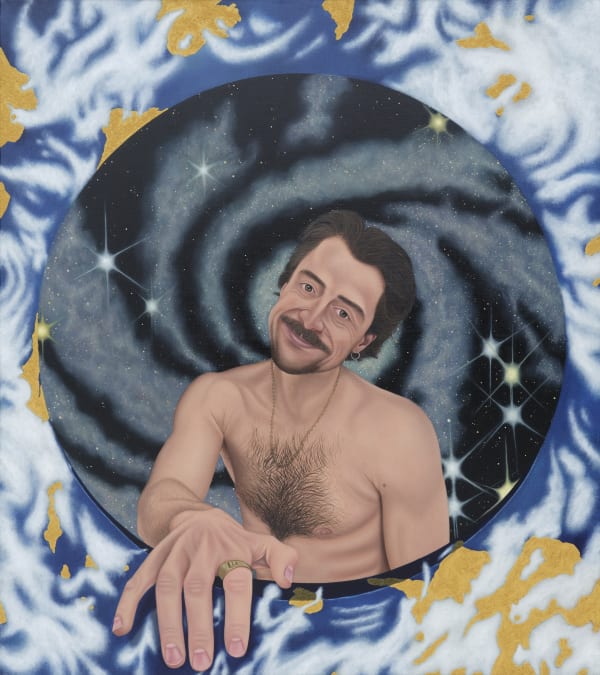

현재 영국을 가로지르는 거대한 정치이념적 균열이 브렉시트로 더욱 깊어졌다는 여론이 돈다. 영국의 유럽연합 탈퇴는 2016년 6월에 실시된 국민투표의 근소한 차이로 이루어졌고, 그 여파로 영국 사회와 경제에 큰 혼란과 지도층의 배임을 직면하게 되었다. 공동체에서 급격히 고립되어버린 여파와 연쇄되어 나타난 사회 속 대립구도와 변화는 많은 런던 기반 작가들의 인물화에도 나타났다. 글렌 푸드바인[Glen Pudvine]의 자화상 <Europe Man(유럽인)>(2024)은 장난기 있고 자족적인 모습과 쪽빛 하늘 위, 주변부로 소용돌이치는 구름과 황금빛 모래 같은 유화 물감으로 점철되어 있다. 이러한 유기적 형태는 아주 높이서 내려다본 섬처럼 느껴지며, 작가의 푸른빛과 금빛 팔레트는 EU 깃발의 색과 조화를 이룬다. 그러나 완벽한 원형의 구성 내부에서 중심이 더 견디지 못하고 소용돌이 속으로 붕괴되어 작가를 미지의 우주 공간으로 빨아들인다. 제목 <유럽인>은 자신의 모습을 미술사적 또는 인류학적 맥락 내에 표하려는 작가의 관심을 이어간다. <Pioneer Man(선구자)>(2023)나 <Glen and Gibraltar I in Perugino(페루지노의 글렌과 지브롤터 I)>(2024)과 마찬가지로 <유럽인> 또한 고금을 동시에 말하나, 여기서 그 대화는 알려진 것과 알려지지 않은 것 사이의 격한 긴장구도를 이룬다. 작가는 유약하나 단호한 모습으로 그 형식적이고 회화적인 물질과 의미의 흐름 중심에 위치한다.

누르 엘 살레[Nour el Saleh]의 섬뜩한 <The rational planning of stillness(정적을 위한 합리적 계획)>(2024)은 동화, 고대 신화, 우화의 도상적 속삭임이 들리는 그림이다. 몸의 형태와 상형문자 사이를 부드럽게 오가는 구상 언어를 사용한다. 분위기는 신비롭고 우울하다. 평면의 공간은 세 명의 여성으로 구성되었다. 망토를 걸친 여성이 길고 가느다란 손가락으로 아래쪽에 있는 나체 여성의 머리 크기를 측정하는 것처럼 보이고, 한 손이 그 둘을 향해 마스크를 내민다. 아래쪽, 무릎 위에 누워 있는 또 다른 머리가 그 내밀어진 마스크를 올려다보고 있다. 피부는 천처럼 캔버스를 가로질러 흐르는 듯, 축 처졌지만 역동적인 모습이다. 이는 생동과 위축을 동시에 암시하는데, 제목의 ‘정적’과 ‘계획’과는 대조구별 구도를 이룬다. 신중과 이성이 전도되어 기정사실을 되짚게 하는 신화가 항상 그렇듯, 누르 엘 살레는 인물의 얼굴이 마스크에 완전히 숨겨지기 직전, 내면 성찰과 명상의 조용한 고통을 포착하며, 분위기와 찰나를 변화시키고, 진실을 허구로 바꾼다. 작가는 창백과 쇠약을 통해 자신의 신비로운 시적 서사 뿐만 아니라 런던에 사는 레바논 여성인 자신의 투쟁을 의미하도록 설계했다. 입 다물고 꼼짝 말라고 강요되지만 완고하게 거부하는 외부인. 이를 통해 그녀는 사회의 특정 파벌이 소외된 소수인들을 가리고 부정하기 위해 만들어내고 주장하는 타자의 고통을 폭로한다.

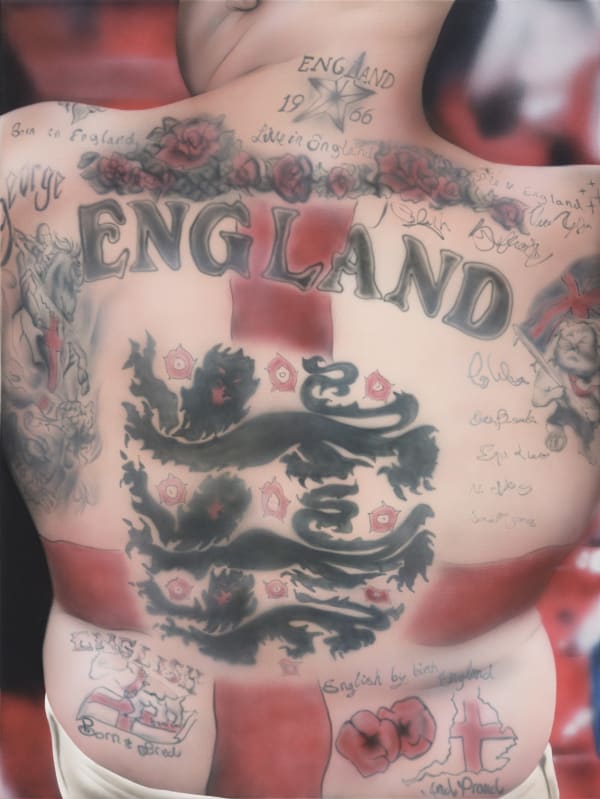

마티아 구아르네라-맥카시[Mattia Guarnera-MacCarthy]의 <Skin Deep(피부 깊숙이)>(2024)는 무너지는 중심과 그 주변부에서 경험되는 격동 사이의 갈등을 함축적으로 보여준다. 관람객은 축구 팬의 문신이 새겨진 등을 마주하게 되는데, 여기에는 잉글랜드 대표팀의 상징인 ‘삼사자’ 문양과 어깨를 가로지르는 ‘ENGLAND’가 새겨져 있다. 성 게오르기우스의 십자가[Saint George’s Cross]가 목, 둔부, 등근육까지 뻗어 나가며 전통에서 국수주의로 통하는 길을 그려낸다. 축구 팬 몸 곳곳의 이미지가 ‘순종 잉글랜드 본토박이(ENGLISH born and bred)’라는 주장을 거듭 확인시켜 준다.

필자가 글을 쓰는 지금, 2024년 파리 올림픽은 세계 많은 이들에게 기쁨을 안겨준다. 하지만 스포츠가 지닌 화합의 힘은 축구 팬의 인종차별적 상징과 언어로 자신의 몸을 표시하는 결정으로 전복된다. <피부 깊숙이>는 문화와 사람들을 하나로 만드는 스포츠 정신을 전복시키며 고집을 부리는 이들의 행태를 적나라하게 보여줌으로써 정체성의 규범에 의문을 제기한다. 이 그림은 연약하고 취약하며 덧없는 피부를 묘사하고 있지만, 그 이면에는 깊이가 결여되어 있다. 마티아-구아르네라-맥카시는 국제 스포츠 행사 기간에 경험할 수 있는 국가적 자부심과는 동떨어진 편협한 ‘영국스러움’을 조명하는 피상적 표면을 만들어낸다. 그의 ‘잉글랜드’는 나의 고향도, 마티아[Mattia]의 고향도 아니다. '어웨이' 경기에서 종종 눈에 띄는 공허한 문신을 통해 구현된 이 남자의 잉글랜드는 지금 영국을 괴롭히는 폭력과 무지를 상징하며, 결과적으로 그 메시지의 연약함과 그것을 몸에 지닌 남자의 경박함을 폭로한다.

III: 바탕과 변화

신체가 상징, 문자, 언어에 의해 이해되고 탐구 되듯이 바탕 역시 활기를 띠면서도 혼란에 빠져 친숙함과 소외감, 신성함과 위험 사이의 분열을 표하며, 'home'과 'away'의 개념 사이의 얽힘을 지속시킨다. 휘슬러[Whistler] 풍의 야경에서, 두 인물이 밤의 고요 속에 스쳐 지나가는 배처럼 서로를 스쳐 지나가는 조슈아 라즈[Joshua Raz]의 <Decompression(감압)>(2024)은 전경의 인물의 입술 가까이에 있는 손에서 나오는 소용돌이치는 연기의 화려한 아라베스크 무늬가 압도적이다. 화면 안쪽으로는 그의 익명의, 일시적 연결고리가 걸어가고 있다. 작가는 둘의 교차하는 순간을 드러내며, 잠시 같은 시공간을 공유하면서도 서로에게 알려지지 않은 채로 남는 모습을 보여준다. ‘홈’이 ‘어웨이’가 되고 ‘어웨이’가 ‘홈’이 되는 찰나를 묘사한다. 불가피하게 상실된 성향의 부드러운 흐름은 밤하늘의 반짝이는 별빛을 향해 올라가는 연기의 소용돌이에서 더욱 깊게 나타나며, 빗방울이나 눈, 또는 재일지도 모르는 점묘로 현란하게 빛난다. 라즈의 인물들은 정형화된 모델링을 보여주지 않으나 오히려 그의 바탕과 풍경의 특징처럼 패턴의 힘과 구성을 통해 물리적, 심리적 잠재력을 확보한다. 따라서 라즈의 <감압>은 주인공의 연기서린 날숨과 함께 매혹적이고 모든 것을 빼앗는 바탕의 조화로운 색채와 소속감에 의해 불가피하면서도 쉽게 포옹되고 억류되는 것을 결합한 것이다. 격변은 여기서 밤의 고요함 속으로, 천천하고 섬세한, 절묘한 속삭임으로 불길함을 고조시키며 작동 중인 감압의 본질과 의도에 대한 정보성을 높인다.

'홈'에서 '어웨이'로의 탈출은 여러 매체를 통해 촉진·가속화될 수 있지만, 영화만큼 확실한 것은 없다. 앤드류 모건 [Andrew Maughan]의 <Collapse(붕괴)>(2024)는 장소가 인물에 가하는 위험과 그 소외와 위험의 본질이 표면 전체에 서서히, 그러나 확실하게 펼쳐지는지, 라즈의 연결고리를 이어간다. 화면 속으로 들어간 관객은 뚜렷하게 미국적이고 서구적인 풍경을 통과하는 자동차 안에 앉아 있다. 말 그대로 캔버스에서 잘라낸 두 개의 눈이 앞과 뒤를 동시에 응시하며, 관객을 불확실의 상태로 포착한다. 관객인 우리는 자발적으로 차에 탑승한 것일까? 도로는 암석의 르푸소아르[repoussoir]에 둘러싸여 결국 압히 막히는데, 이를 오래 바라볼수록 더 육감적이고 묘해진다. 모건이 이 테라코타 암석 부분을 녹색, 파란색, 보라색으로 밑칠했음을 고려하면 당연한 묘함일지 모른다. 크림과 버터 같은 살결을 그런 방식으로 조제한 루시안 프로이드[Lucian Freud]의 회화적 전략을 차용한 것이다. 마치 할리우드 영화에서 나온 것처럼 너무나 친숙한 장면이 기쁨과 공포 사이를 오가는 것이다. 우리가 인지하는 유일한 인물은 주인공인 '위대한 암살자[The Great Assassin]'의 공허한 뱀파이어 같은 반영이다. 마찬가지로, 바탕은 뉴스를 통해 보게 되는 분쟁 지역의 시체 더미를 암시하는 지질학적 특징이 분명 지배적이다. 모건[Maughan]이 말하는 붕괴는 단순히 이성의 붕괴가 아니라 가장 고통스러운 희망의 붕괴다. 우리는 그와 그의 복면 자객과 함께 목적지나 목적을 알 수 없는, 아무데도 가지 않는 길을 따라 여행하며 아무도 풀 수 없는 수수께끼로의 여정이 주는 혼란 만을 느낀다.

라즈의 바탕이 장식의 풍요로움, 모건의 바탕이 형태의 관념적 단순성을 보였다면, 제임스 오웬스[James Owens]의 바탕은 하이브리드형이다. 독특한 솔직함을 제공하면서도 떨리는 선과 색채의 꽃다발로 구성되도록 허용한다. 인물의 내면은 다시 한 번 설명과 정교화로 알려지지만, 오웬스가 의도적으로 사용하는 스킴과 스키마의 나레이티브로 더욱 증폭된다. <I'm sorry, I have to be with my pigs(죄송합니다, 제 돼지들과 함께 있어야 해요)>(2024)는 그 위선적인 의식[faux naïf]의 장면을 즐긴다. 호박색과 비취색 톤으로 빛나는 식물과 동물의 에덴 동산 같은 정원에 큰 흰색 슈미즈를 입은 젊은 남자가 앉아 있는 여성에 기대어 앉아있다. 배경의 왼쪽 사분면에는 커다란 빨간 텐트가 관객의 시선을 끌어당긴다. 그 아래에는 문제의 돼지 한 마리가 보인다. 가능성이 충만한 이 장면은 헤어지는 연인으로 해석될 수 있다. 남자는 작별을 고하고 양돈장으로 되돌아가는 것이고 여자는 서커스 텐트로 돌아가 마을을 떠나 다른 지역으로 가는 것이다. 혹은 그녀가 그를 떠나며 공연하는 서커스 돼지를 치러 가는 것일 수도 있다. 해석은 물론 유연하며 그림을 보는 데 있어 어떤 결론도 내지 않는다. 여기서 중요한 것은 두 인물 사이, 일시적 연결의 묘사다. 한 명은 집에서 외부로 나온 것이고, 다른 한 명은 외부에서 집으로 돌아간다. 오늘날 다수의 영국인이 경험하는 이주의 문제를 적절한 뉘앙스로 부드럽게 말하며, ‘장소’라는 고르디우스의 매듭[Gordian knot] 안에서, 그리고 화면 속 인물들의 안전을 카멜레온처럼 교란시키는 색채의 변화무쌍한 모자이크 안에서 자신을 나타낸다. 세 작가의 작품세계 속, 무엇도 고정된 바 없지만, 관객은 각 동작이 서로 소통하는 소동이 되어 느린 동작으로 펼쳐지고, 인물, 바탕, 그리고 궁극적인 경쟁의 주체성이 교란되고 재조정되면서 슬로모션으로 체감하게 된다.

IV: 신화와 물질

구상은 항상 과정, 주제, 대상, 즉 일련의 ‘라이트모티프’를 통해 자신을 풀어냈으며, 작가로 하여금 표피 이면 뿐만 아니라 그 껍질을 벗기고, 느끼고, 침투할 수 있게 하는 상황의 질감을 탐구할 수 있게 했다. 바탕이 인물을 변동과 추상의 도주로 내던질 수 있듯이, 고대와 현대의 신화의 전당 역시 인물, 그리고 인물이 절개하는 주제들을 더 잘 탐구할 수 있는 유사한 플랫폼을 만들어낼 수 있다.

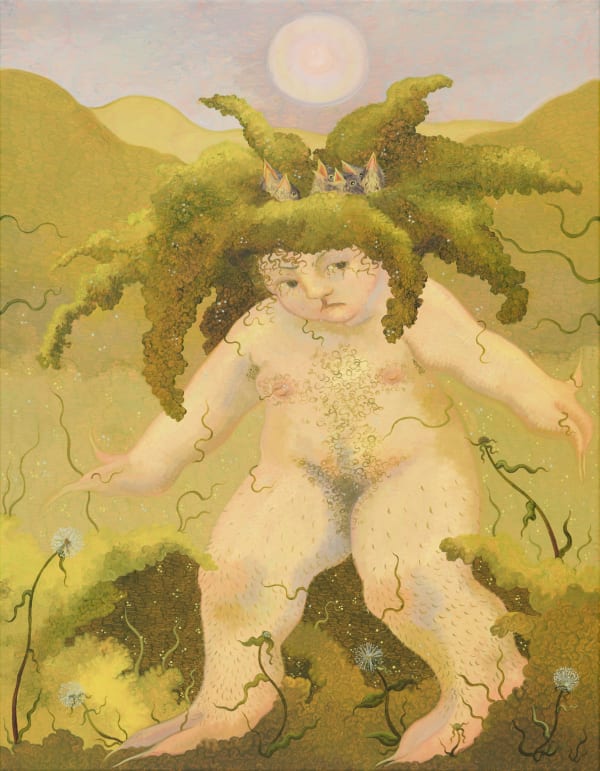

게오르그 윌슨[Georg Wilson]의 <Heavy Is This Head(이 머리는 무겁다)>(2024)는 영국 시골과 관련된 여러 신화의 흐름을 엮어내며 이를 통해 역사적 소유권, 토지 접근성, 그리고 궁극적으로는 계급 구조에 대한 중요한 질문을 던진다. 윌슨은 신화나 전설 속의 요정 같은, 성별이 모호한 인간형태의 생물로 화면을 채우는데, 이들이 목가적인 환경과 교감하는 모습이 매력적이고 도전적이다. 여기서 식물 같은 손과 발을 가진 꽤 매력적인 인물이 불편한 듯한 시선으로 그림 밖을 내다보고 있다. 생울타리로 만들어진 듯한 큰 머리 장식은 축복이지만 버겁다. 넝쿨 줄기들이 머리 장식을 향해 기어가 더욱 무거워 보인다. 아마도 이 인물은 발아와 쇠약의 이분법을 말하고 있는 것 같다. 여러 영향 영역에 걸쳤겠으나 여기서는 아발론이나 카멀롯의 진부한 시골에서 생명을 이끌어내어 얻어 정체성과 권력에 대한 대화로 관객을 이끈다. 따라서 윌슨은 신화에 내재된 알레고리와 전설의 고상한 에너지를 장소, 지위, 온전성에 대한 현대적 반대심문으로 대체한다. 이 모든 것은 시적인 미완성에서 즐거움을 느끼는 변덕스러운 인물에 의해 명확히 표현되지만, 그 연장선에서는 현재 시제로 명확히 말하는 불확실성과 불안을 자극한다.

윌슨의 달콤쌉싸름한 변덕은 소피 루이그록[Sophie Ruigrok]의 작품에서 계속된다. 다만, 윌슨의 주인공들이 집을 이야기하면서도 먼 곳에서 온 것처럼 보이는 반면, 루이그록의 인물들은 어디에도 속하지 않는 고통과 위안 속에 유예된, 가사 상태로 보인다. <Salt Water(소금물)>(2024)에서는 머리 둘이 금색과 녹색의 유리질 바탕 위로 떠 있다. 둘 다 눈을 감고 있으며, 조용히 물 위로 떠다니며 얼굴을 가로지르는 흰 줄무늬로 반짝이는 햇빛을 받고 있다. 이 평온한 장면은 이 머리들이 실제로 쉬는지, 아니면 또 다른 상황인지 의심을 던질 때 균열되기 시작한다. 이 인물들은 살아있는 것일까, 아니면 어쩌면 끔찍한 난파에 의해 바다에 떠 있는 것일까? 신화의 렌즈를 통해 우리는 이미지의 지표를 다른 방향으로 돌릴 수 있다. 물에 떠 있는 머리들은 즉시 세례의 행위와 궤적을 떠올리게 한다. 그러나 이러한 장면은 영국 해협을 소형 선박으로 건너려다 죽은 난민들을 생각할 때 무거워진다. 작가는 실제로 이 물이 소금물임을 강조한다. 안타깝게도, 신화적 규모의 동시대적 비극과 일상을 제공하는 내러티브다.

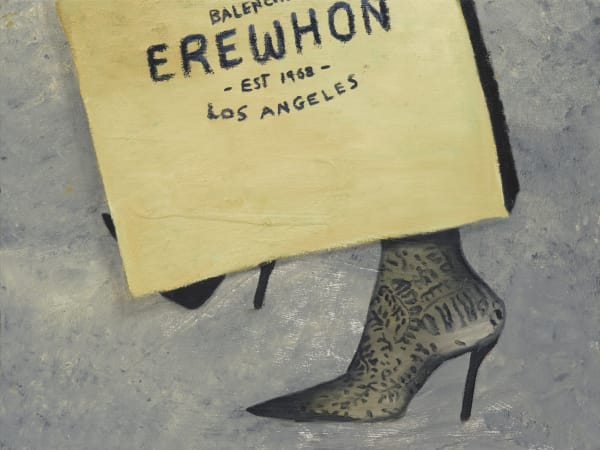

역사, 문화, 종교, 정치는 다양한 신화적 의미의 그림자를 드리운다. 윌슨의 요정들과 루이그록의 버려진 머리들이 조용한 불안의 상태에 고정되어 있으면서도 그러한 담론에 색을 더하듯이 루비 딕슨[Ruby Dickson]의 인물들 또한 우리가 '유명인'이라 일컫는 현대 신화의 삶을 누른다. 윌슨과 루이그록의 주인공들의 섬세하고 충족한 침묵과 달리, 딕슨의 인물들은 유명인의 등장을 떠들썩하게 알리는 캔버스를 차지한다. 딕슨의 <Kim Kardashian is seen out and about in Midtown, October 07 2023, New York City(킴 카다시안이 2021년 10월 7일 뉴욕시 미드타운에서 외출하는 모습)> (2024)은 리얼리티 TV 스타가 분홍색 옷을 입고 작은 은색 핸드백을 들고 있는 모습이다. 바랜 목탄색의 대각선이 화면 속 색채와 폭발한다. 사회의 어리석은 관심사, 즉 패션이나 스캔들과 같은 호기심거리가 무대 중심을 차지하지만 윌슨과 루이그록의 인물들처럼 딕슨의 인물도 그녀의 이미지와 그것을 형성하는 지표들을 고양시키고 더욱 문제시할 만큼의 변절을 드러낸다. 여기서 카다시안의 사진은 의도적으로 잘렸다. 단두대에 윗부분이 잘린 것처럼 유명인을 현대판 마리 앙투아네트로 만들어버린다. 이러한 테마는 그림이 일종의 이폭화라는 점에서도 반복된다. 딕슨이 유명인의 얼굴을 제거한 체로 복장에만 초점을 맞춘 것은 모든 신화에서 동일하게 말하는 경고와 상통한다. 어떠한 텍스트도 절개하고 파들어 들어갈 수 있는 만큼의 깊이, 그 이상은 없다는 것이다. 관객, 독자, 또는 신봉자, 그 누구든 간에 동일하다. 따라서 인물은 자신의 몰락의 주체가 되며, 가해자이자 피해자가 된다. 무엇보다 중요한 것은 인물이 환상의 총체 속에서 비난하지만 받아들여야만 하는 환상의 총체 속에서 ‘무엇을 대변하느냐’이다.

V: 정적(靜的), 정적(靜寂)

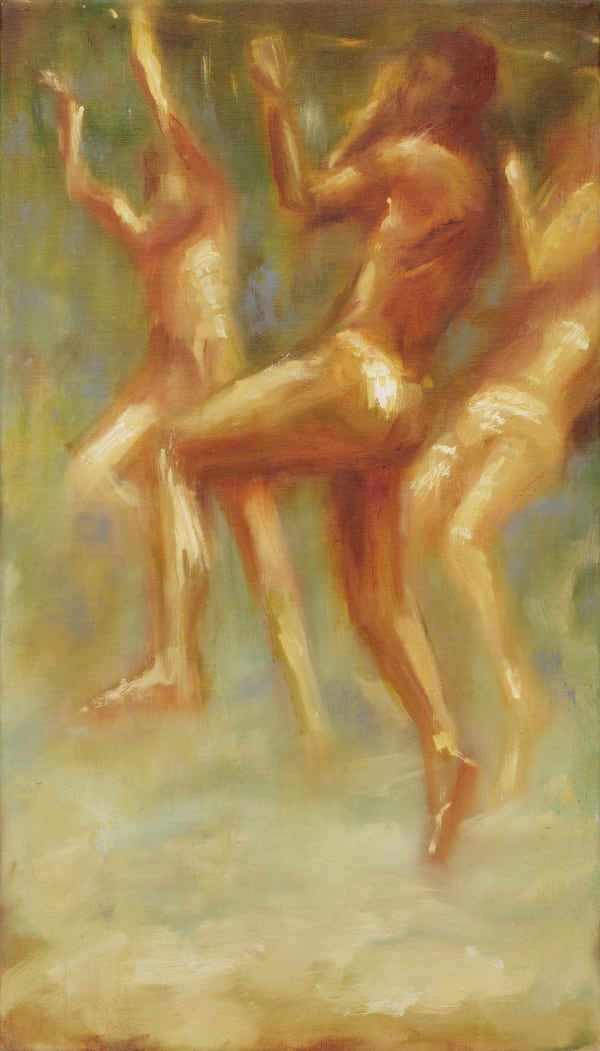

고요 속에 동요가 있다. 오늘날 많은 구상 화가들은 가능성이 농후한, 벨벳처럼 매끄러운 침묵을 제시하며 평면은 부인할 수 없는 기대감으로 진동하여 관능과 공포 사이를 오간다. 중국 태생이지만 바르셀로나에서 살며 작업하는 페이 왕[Pei Wang]은 루비 딕슨처럼 패션 세계에 초점을 맞춘 작품을 만들었다. 그러나 왕의 작품 속 디자이너 의상을 걸친 모델들은 화려한 색채나 찬사의 표현이 없다. 오히려 은잿빛 팔레트로 동요하는 듯한 거친 붓질은 인물들을 자신만의 어두운 신기루가 되는 공간에 가둔다. 본래 그 공간은 디자인을 식별하고 기념해야 할 곳이지만 작가를 통해 소원해지고, 멀어지며, 심지어 부조리해진다. 루벤 베렌 제임스[Reuben Beren James]도 비슷한 팔레트로 밀랍 층 사이 잉크로 작품을 제작했다. 인물의 얼굴과 몸을 축약하거나 침대 위 두 인물의 포옹을 다양한 상태로 포착한 일련의 작품이다. 여기서도 표면은 옛 할리우드 누아르 필름처럼 부드럽게 깜빡이며, 이러한 시각적 입자화는 관객을 사로잡고 시험하는 역할을 한다. 그 결과로 이미지는 발견된 것(found image)이자 조작된 듯한 모호성으로 호기심과 이를 자아낸다. 표면의 대담하면서도 묘하게 균질화된 분위기에도 불구하고 그들의 침묵의 시에 도취되어 관객을 관음객으로 만든다.

페이와 베렌 제임스의 그리자유[grisaille]가 담은 조용한 수수께끼는 크리스토퍼 하트만[Christopher Hartmann]의 매력적인 <Untitled(무제)>(2024) 속 고요와 혼돈의 장면으로 연결된다. 의심할 여지 없이 뜨거웠던 두 남자의 나눔이 일렁이는 파도가 되어 침대를 가로지르고 눌린 쿠션과 주름진 시트 위로 굽이친다. 정물화이자 풍경화인 이 작품은 흐르는 시냇물처럼 화면 구성을 따라 흘러내리는 쿠사마의 점이 연상되는 침대 덮개로 더욱 화려해진다. 무엇보다 하트만이 구성한 무대 위 핵심은 침대 위에 흩어진 캘빈 클라인 속옷과 양말이다. 양말 발목 입구의 커다란 구멍과 널부러진 속옷의 부풀음을 주목하라. 달아오른 순간의 유물 이상으로, 이 옷가지는 그 옷을 벗 음으로 가능해진 바로 그 행동의 양상을 포착한다. 하트만은 침대조명 속 유혹적인 무대를 통해 관능적 박동을 더하지만 분위기는 여전히 부드럽고 사색적이다. 하트만은 추상을 구상으로 변태시키고, 정적·객관적 순간의 명상을 동적·주관적 공간의 확장된 고찰로 펼치는 작가다. 그는 당신을 관객으로, 그의 대상을 주체로 만들며, 인물이 왔다가 사라졌을 때에도 평안 하며, 저 멀리서 침묵을 울리고 정적을 일으키는 화가다.

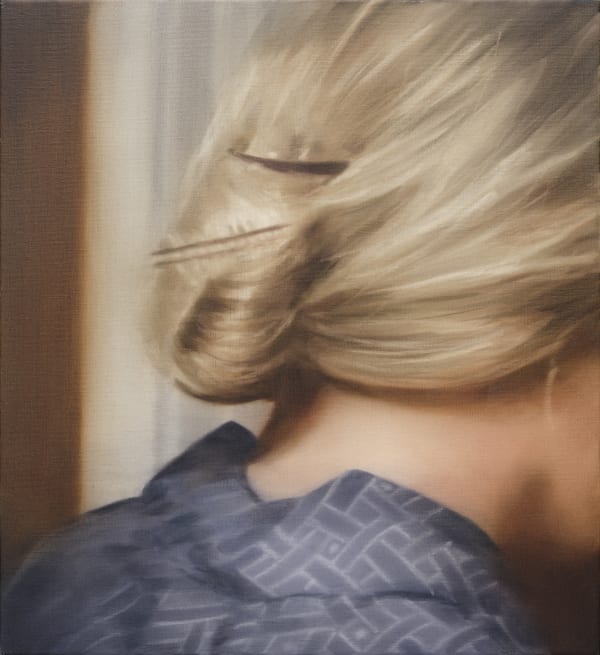

레이첼 랭캐스터[Rachel Lancaster]의 그림 속 인물은 더 많은 축약으로 그렸다. <Arms Reach(손이 닿는 곳)>(2024)는 여성의 뒷머리와 깔끔하게 땋은 머리가닥에 초점을 맞춘다. 회화 표면은 부드럽고 유백색이며, 이미지의 부연 안개에도 불구하고 게르하르트 리히터[Gerhard Richter]의 사진회화[photopaintings]를 연상시키는 볼륨감에 주의를 기울인다. 이러한 그림의 연함은 작품의 제목과 대비를 이룬다. <손이 닿는 곳>은 등을 돌린 인물과의 거리나 위치를 고려할 때 곧 폭력이 행사될 것을 시사한다. 유연했던 것이 이제는 부들거린다. 그림자는 더 이상 인물을 모델링하지 않고 조용한 정적 상태로 걱정하게 만들며, 인물이 근미래 안녕할 것인지 의문을 제기한다.

VI: 홈 앤 어웨이

이 에세이는 마지막으로 아론 포드[Aaron Ford]의 작품을 살펴보고 마무리된다. 그의 <Two Women with Vases(꽃병을 든 두 여인)>(2024)에 등장하는 두 인물에서도 부드러운 평온함이 비슷하게 배어 나오지만 유동적이고 호기심 얽힌, 약간은 불안정한 선이 반전이다. 두 인물 모두 커다란 꽃병을 들고 있다. 좋은 일을 기리는 꽃다발이 담겨야 할 장식품이자 실용적인 물건이지만 비어 있다. 주황색 옷을 입은 인물은 꽃병을 보호하려는 듯 가까이 들고 있고, 다른 한 명은 휴대폰 너머의 목소리에 귀 기울이고 있다. 두 인물 모두 시선이 아래를 향하여 이미 고요한 정적에 우울의 무게를 더한다. 어떠한 상황이 가깝다는 느낌이 진동하는 분위기는 꽃병의 의미를 재구성한다. 꽃이 아닌 사랑하는 사람의 유골을 담기 위한 것, 그 소중했던 기억을 담기 위한 유골함일지도 모른다.

포드의 초상화 속 두 인물은 실제 작가의 친구들로, 가족 역학 관계와 가족정치를 이야기한다. 두 여성은 런던이 자라난 고향이지만 가족은 그렇지 않은 경우다. 화면 우측 상단, 벽에 걸린 액자 사진은 오래전 이란에서 온 것으로, 우측에 앉은 여성 사르빈[Sarvin]의 자랑스러운 문화유산과 정체성을 가리킨다. 이 골동품처럼, 사르빈이 조심스럽게 보호하는 꽃병 겸 유골함은 단순한 추모의 행위가 아니라 세대 간의 영속성을 지키기 위한 행위가 된다. 말하자면 바톤을 전달하는 것이다. 또한 포드가 유리를 묘사하는 데 관심을 가지고 있다는 점도 주목할 필요가 있다. 유리는 꽃병과 물질적으로 조화를 이룬다. 유리와 정체성은 작동 기제가 여러모로 유사하다. 둘 다 경험의 표현 또는 이해의 렌즈가 된다(물론, 그러한 경험은 항상 유동적이다). 유리는 드러낼 수도 있지만 왜곡할 수도 있으며 명확할 수도 있지만 오목하거나 볼록한 타자성으로 관객을 속일 수도 있다. 사르빈의 골동품과 화면 속 꽃병들처럼 유리는 과거가 필히 현재함을 보여주며, 영국에 사는 이 여성들의 미래를 이야기한다. 그 미래는 다채로운 타자성의 만화경이 되어 환영 받아 마땅하지만 현실이 꼭 그렇지만은 않다.

혈연이든 택하여 이룬 식구든 ‘가족’은 이 에세이의 시작점으로 회귀하여 '홈'과 '어웨이'의 개념을 상반관계로 이해할 필요가 없다는 결론에 다다른다. 인종, 피부색, 신앙을 불문하고 모든 사람들과 그 가족은 한 곳에 공존할 수 있으며, 그 공존의 장소를 '집'이라 부를 권리가 있다. 이 작가들이 공유하는 인물들의 다양한 모습 속에 그러한 비전이 공유된다. 그들의 모습이 잘리거나 축약되었거나, 연약하거나 환상적이든, 현재하거나 부재하던지 말이다. 그러한 공존이 가능한 영국을 그려보려 노력하는 그림들이 우리 앞에 남았다. 단순히 개인 또는 국가 차원의 정체성에 기반한 것이 아닌 전인류를 위한 힘과 선에 따라 움직이는 것이다. 미술의 역할은 우리 모두에게 그 반성의 거울이 되고 표현과 고백, 희망의 한 조각을 건내는 것 아닌가?

2024년 8월 5-8일

빌트셔 샌디레인에서,

매트 캐리-윌리엄스

EPISODE II: HOME AND AWAY,

CONTEMPORARY FIGURATIVE PAINTING IN BRITAIN

I: THEN AND NOW

The highlights reel of British painting rarely deviates from the vocabulary of figuration. One can hopscotch from the silky swish of van Dyck, Gainsborough and Reynolds to the fleshy funk of Moore and Spencer, then skip across the darkened throb channelled by the stars of the School of London and finish with a flourish provided by the cool yet erotic, simple yet sardonic beats of Hockney and Saville. All these artists have, in their most crucial and successful moments as painters, elevated the human figure to something other than its physical form. On their watch the body has signified an array of concerns predicated upon various tributaries of status and became a vehicle that emblematized a certain class or identity; certain patterns and paradigms of desire and their ever-shifting geology of being and becoming.

Nearly all these artists began – and, in many cases, continued – their careers in London. Yet nearly all were not born in London nor, indeed, were they born in Great Britain. Van Dyck was born in Antwerp; Francis Bacon was Irish; Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach were both born in Berlin. Hockney, like Moore, was a Yorkshireman. So, whilst the great triumph of British figurative painting was heralded in London’s art hotspots such as Kensington, Camden, The Royal College of Art or The Royal Academy, its germination often began in the quieter, bucolic countryside offered by counties such as Suffolk or Devon.

Home and Away – as both title and conceit; journey and oxymoron – is an Episode that embraces such historical dissonance – of source and celebration - even as the contemporary artists it explores betray an association of subject, mood, and design. Fourteen painters, most of whom now call London their home and have enjoyed formative experiences as artists in the British capital, have been brought together across two exhibition sites: Gallery 2 in Seoul and Matt Carey-Williams in London. A show – for me as curator and author – that sits in that space both home and away, disconnected physically yet personally connected emotionally and professionally for me. Many of the artists included in this exhibition, like so many generations before them who now so profoundly colour our understanding of ‘British art’, were born outside of London and the United Kingdom yet, today, their practices speak to a renewed interest in and examination of figurative painting in Britain. Painters born with Italian and Ghanian parentage; to German and Costa Rican parents or hail from Lebanon join those born in Chester, Colchester, Newcastle and, yes, even London to collectively paint a tapestry of experience that reflects what it means to live in Britain today. The exhibition thus serves a multilaminate of oppositions and congruities that, when contemplated thousands of miles away, further amplifies the issues that both entangle such a dazzling variegation of practice and politics yet lubricate a shared chorus of passion, presence, and protest.

II: CENTRE AND PERIPHERY

As I write this essay parts of Britain are burning. Several violent riots, instigated by numerous members of various far right factions, have resulted in hundreds of arrests across the country thus far. One of the more disgusting, barely believable images was of thugs deliberately burning down asylum hotels in Rotherham and Tamworth. A screaming mob literally smoking out frightened refugee families so that they could attack them for simply being different to them. When Yeats’ centre no longer holds, it is those on the periphery that experience the wildest tectonic shifts of logic, reason and care, and it is from this peripheral plane of anxiety and agitation – experiential and intellectual; political and racial – where much of the work in Home and Away reverberates.

Many people believe that the great contemporary political chasm that currently bifurcates Britain was exacerbated by – and remains exaggerated because of – Brexit. With a slim majority, Britain’s referendum held in June 2016 led to the country’s eventual exit from the European Union. The ramifications of that decision have served perplexity and dereliction to Britain’s economy and society in equal measure. Such a sharp political shift from community to isolation, accompanied by the multitude of antagonisms that flesh out that shift, has shaped many London-based artist’s appreciation of the figure. Glen Pudvine’s Europe Man (2024) sees his cheeky, almost self-satisfied self-portrait cling on to a compositional periphery of swirling clouds laid over an azure sky which are then punctuated with golden, sandy swathes of oil paint. These organic forms feel like islands seen from far above and Pudvine’s palette of blue and gold here chimes with the colours of the EU flag. However, inside the composition, marked out as a perfect circle, the centre does not hold but, rather, creates a galactic vortex aimed at sucking the artist back into the unknown of outer space. The title continues Pudvine’s interest in images that position his own likeness in art-historical or anthropological contexts: like Pioneer Man (2023) or Glen and Gibraltar I in Perugino (2024), Europe Man speaks to both past and present but, here, that conversation becomes a tense battle between known and unknown, with the artist – vulnerable yet resolute – positioned at the centre of that formal, painterly flux of matter and meaning.

Nour el Saleh’s haunting The rational planning of stillness (2024) is a painting that whispers the iconography of faerie tale, ancient myth and parable with a figurative language that silkily morphs between corporeal form and hieroglyph. The mood here is mystical and melancholic. Three women occupy the pictorial space: a cloaked figure seems to calibrate the size of a naked woman’s head below her with her long, spindly fingers as a hand thrusts forward a mask towards them both. Below, lying in a lap, another head stares up at the offered mask. Flesh, like fabric, seems to flow across the canvas in runny rivulets of oil - sagging yet dynamic – that simultaneously suggest both animation and atrophy which, in turn, sits in contradistinction to both the stillness and analysis indicated in the title. However, as with all myths where prudence and reason are often inverted to interrogate pillars of assumed truths, so it is here that Nour el Saleh manages to capture the quiet agony of inflection and contemplation shortly before the mask fully covers the central figure’s face, transforming mood and moment, shifting truth to fiction. Etiolation and emaciation are inevitably designed by the artist to speak not just to the cryptic mystery of her poetic narrative but to signify the struggle of herself as a Lebanese woman living in London. The outsider, told to be still, yet who remains adamantly not. In so doing she powerfully unmasks the distress of a viscous alterity, manufactured and propounded by one faction of society to mask and deny a marginalised minority.

Mattia Guarnera-MacCarthy’s Skin Deep (2024) neatly sums up the contest between a crumbling centre and the maelstrom of friction those on its edges experience as a result. The viewer is presented with a football ‘fan’s’ (perhaps ‘hooligan’ is a better word) tattooed back. Emblazoned at the centre is the heraldic motif of three lions that make up the England football team’s crest or badge. Above it ‘ENGLAND’ is scribed in dark and heavy letters across the figure’s shoulders. The cross of Saint George radiates out towards the neck, buttocks and two latissimus dorsi of the figure, tracing a path from tradition and even celebration (purloined from the Byzantine just as Pudvine’s trompe l’oeil hand is taken from the High Renaissance) to the pathetic, deplorable language of nationalism and racism. Numerous vignettes record the figure’s repeated affirmation that he is ‘ENGLISH born and bred’.

The capacity that sport should – and so often does – bring people together (written as the Olympics continues to bring such joy to so many people across the world) is now violated by the determination of this figure to permanently mark himself with the language and symbology of xenophobia and prejudice. Skin Deep thus speaks to the canon of identities, exposing the preposterous lengths certain people will go to for such marked self-determination even as it hijacks sports that intend to bring all cultures and peoples together as well as openly denigrate those who sit outside of their orbit of identification. This is a painting of skin – flimsy, vulnerable, easily shed – but it is far from deep. Guarnera-MacCarthy has created a surface of superficiality that interrogates rare, specific but all too often heard perspectives of Britishness that are (thankfully) anathema to the pride one ordinarily feels for one’s national football team during an international tournament. This man’s England is not my or Mattia’s home; it is a state made manifest by this figure-cum-wraith with perfunctory, empty tattoos, usually on display at ‘away’ games, that now shrill a violence and ignorance which currently plagues Britain, but which ultimately betrays the fragility and insipidity of the message and of the fatuous man whose paper-thin skin bears it.

III: GROUND AND FLUX

As the body is interrogated by symbol, glyph and language, so too is the ground energised yet infuriated into a flux that speaks to the divisions between familiarity and alienation; sanctity and peril and which continues the entanglement between notions of ‘home’ and ‘away’. In a Whistleresque Nocturne, two figures pass each other like ships in the night. Joshua Raz’s Decompression (2024) is dominated by an ornate arabesque of swirling smoke, emanating from the foregrounded figure’s hand closest to his smoking lips. Further into the composition walks his anonymous, temporary connection. Raz unveils a moment where two people cross paths and, just for a moment, share the same time and space, whilst all the while remaining unknown to one other. The artist thus delineates a split second where home becomes away and vice versa. The gentle flux of a propensity inexorably lost is more profoundly announced in the swells of smoke that circle up to a glittering, starry night sky, dazzling with flurries of pointillist marks that could be rain, snow, or falling ash. Raz’s figures do not betray any modelling in the usual sense but, rather, attain their physicality and psychological potency through the power and orchestration of pattern, much as his characterisation of the ground and ‘scape does. So it is that Raz’s decompression is here both the smoky exhalation of his protagonist combined with their ineluctable yet effortless embrace then detention by a seductive, all-consuming ground of choreographed colour and affiliation. Upheaval speaks slowly and delicately here – deep into the quite of the night – which, in turn, makes such exquisite whispers even more ominous, begging yet more information about the nature and intent of the decompression at play.

The escape from ‘home’ to ‘away’ can be facilitated and accelerated through several media but none more profoundly that film. Andrew Maughan’s Collapse (2024) continues Raz’s nexus between the perils that place inflicts on the figure and how the marrow of that estrangement and endangerment slowly but surely unfolds across the painted surface. Here, the viewer sits inside a car speeding through a distinctly American – and Western – landscape. Two eyes, literally cut out of the canvas, stare both forwards and backwards, arresting the viewer into a state of uncertainty: are we in the car voluntarily or not? The road is surrounded by (and ultimately blocked) by repoussoir of rocks that the longer you look at them, the fleshier and stranger they become. Fitting given that Maughan prepared these passages of terracotta rock with green, blue and purple underpainting, employing the painterly strategy of Lucian Freud who prepared his creamy, buttery flesh in that manner. So it is that the scene before us, so familiar that it could have been borrowed from any number of Hollywood movies, bounces between delight and dread. The only figure we feel is the vampiric reflection of nothingness that is his protagonist, ‘The Great Assassin’. The ground is, likewise, dominated by a geology that clearly alludes to the piles of bodies we see on the television every day in the many conflicts that haunt it. The collapse of which Maughan speaks is the collapse not just of reason but, most agonisingly, of hope. We journey with him and his masked assassin down a road to nowhere that offers no clarity of purpose or destination, just the frazzle of a journey into a conundrum no one can solve.

If Raz’s ground reverberates with the opulence of ornamentation and Maughan’s with an ideogrammatic simplicity of form then James Owens’ grounds are hybrids, offering both a curious candour whilst still allowing his composition to effloresce in bouquets of colour managed by a commanding yet often tremulous line. The interior flux of the figure is, again, heralded with klaxons of description and elaboration but is further amplified by the narrative – as both scheme and schema – that Owens deliberately employs. I’m sorry, I have to be with my pigs (2024) revels in its faux naïf scene: a young man in large white chemise, supported by a seated female figure, sits in an Edenic garden of flora and fauna glowing in amber and jade tones. In the background a large red tent draws thew viewer’s eye towards the upper left quadrant. Just below the tent one finds one of the pigs in question. The scene, redolent with possibility, could be read as two parting lovers; he is saying goodbye to her as she goes back to the circus tent and heads out of the village it had just entertained whilst he goes back to his farm to tend to his pigs. Or perhaps she is leaving him and taking her performing circus pig with her. The interpretation is, of course, malleable and does not represent any conclusion for the painting’s viewing. What matters here is the rendition of a temporary connection between two actors – one from home; the other away and vice versa – who gently speak to the whiffs of dislocation experienced by so many in Britain today and which, formally, at least, register themselves inside the gordian knots that make up the puzzle of place as well as the shapeshifting mosaic of colours that chameleonically disrupt the security of the figures before us. Nothing stays still in all three of these artists’ universes and yet the viewer cannot help but feel that action unfolding in slow motion with each motion becoming its own commotion, discombobulating and recalibrating the agency of figure, ground and their ultimate contest.

IV: MYTH AND MATTER

Figuration has always unravelled itself – as process, subject and object – as a series of leitmotifs, empowering the painter to explore not just what lies under the skin, but the texture of circumstances that enables that skin to be peeled back; perceived; penetrated. Just as the ground may throw the figure off into fugues of fluctuation and abstraction, so can temples of mythology – ancient and modern – create similar platforms upon which both the figure, and the subjects it dissects, are better interrogated.

Georg Wilson’s Heavy Is This Head (2024) knits together various streams of British mythology that relate to its countryside, in so doing asking important questions about historical ownership, land access and, ultimately, class structures. Wilson populates her paintings with a series of creatures; elfin-like, gender-fluid humanoids born of myth and lore that engage with their bucolic environment in charming yet testing ways. Here a rather winsome figure with botanical hands and feet looks out of the pictorial space as if in some discomfort. They are both blessed and burdened with a large headpiece fashioned, it seems, out of hedgerow. The figure is further weighed down by strands of green, weedy foliage slithering towards the headpiece like hungry spermatozoa. Perhaps the figure here speaks to the binary of germination and enervation; an antistrophe that colours several spheres of influence but which, here, is brought to life in the consciously cliché countryside of Avalon or Camelot, drawing the viewer back in to a conversation about identity and power. Wilson thus replaces the venerable energy of allegory and legend innate to mythology with a contemporary cross-examination of place, status and integrity. All of which is articulated by a whimsical figure that delights in its poetic inchoateness but which, by extension, fuels an uncertainty and anxiety that clearly speaks in the present tense.

Wilson’s bittersweet whimsy is continued in Sophie Ruigrok’s work, however, where Wilson’s protagonists speak of home yet seem to hail from somewhere far away, Ruigrok’s figures are clearly identifiable as human yet seem suspended in the ache and solace of nowhere. Salt Water (2024) sees two heads floating in a glazy ground of golds and greens. Both figures have their eyes closed, quietly drifting in the water catching the sun’s rays which flicker in white striations across their faces. The gentle calm of the scene begins to crackle when we ask whether these heads are resting or, darkly, are not. Are these figures alive or are they floating in the sea, the tragic victims of a terrible wreck, perhaps? It is through the lens of mythology that one can swing the index of the image in different directions. Heads bobbing in water immediately recall the act and arc of the Baptism. However, such imagery – and especially in salt water as the artist is so keen to substantiate – sounds far graver notes when one thinks of all the refugees who have died whilst trying to cross the English Channel in small boats. A different type of narrative that, sadly, offers us a present-day pathos and bathos of mythic proportions.

History, culture, religion and politics all shade various streams of mythological signification. Much as Wilson’s pixies and Ruigrok’s abandoned heads serve to colour such discourse whilst remaining (trans)fixed in states of quiet angst, Ruby Dickson’s figures also press the flesh of the modern myth we now call ‘celebrity’. Unlike the delicate, mauve silence of Wilson and Ruigrok’s protagonists, Dickson’s figures trumpet their own starry arrival in dynamic canvases depicting celebrities. Dickson’s Kim Kardashian is seen out and about in Midtown, October 07 2021, New York City (2024) sees the reality TV star captured in a pink outfit holding a small, silver handbag, driving forward with a chromatic bang out of a picture plane of charcoal, washy diagonals. Society’s thirst for follies such as fashion, notoriety or mahatma take centre stage here but, as with Wilson and Ruigrok’s figures, Dickson’s figure betrays enough tergiversation to elevate and further problematize both her image and the indices that shape them. Ms. Kardashian, here, has been deliberately cropped by the artist; guillotined at the top, turning the celebrity into a modern-day Marie Antoinette: a mood continued by the fact of the painting being a diptych, of sorts. Dickson’s removal of her star’s face and her concomitant focus on merely the clothes that the celebrity wears issue the warning that all myths confess. That the skin of any text is only as deep as the cut you – as viewer, reader or believer – inflict upon it. The figure thus becomes the agent of their own demise, both assailant and victim. What matters is what the figure stands for in the panoply of illusion it inveighs against but must always accept.

V: STASIS AND SILENCE

There is disquiet in the quietness. Many of today’s figurative painters offer a velvety silence so pregnant with possibility that it hums with undeniable expectation, oscillating between erotic titillation and stupefying dread. Pei Wang, Chinese but now living and working in Barcelona, has made a body of work that, like Ruby Dickson, focuses in on the world of fashion. However, Wang’s descriptions of models in review images, wearing a designer’s clothes and laid out in order of a pending runway show, do not offer any pyrotechnics of colour or acclaim. Rather, their grainy application, trembling in a palette of silvery greys, locks the figures into a space that becomes its own dark mirage. A space that should identify and celebrate design but which, in Pei’s hands, becomes estranged, distant, even absurd. A similar palette is employed by Reuben Beren James in a series of works executed in ink suspended between layers of encaustic wax that depict abbreviations of the face and body or reveal an embrace between two figures on a bed, captured in various states of detail by the artist. Again, the surface here gently flickers like an old Hollywood film noir, with such visual particulation serving to both arrest and test. The result are curious, wondrous images that feel as found as they are fabricated, turning viewer into voyeur as we revel in their poetry of silence, in spite of their bawdy yet strangely homogenised ambience.

The hushed enigma of Pei and Beren James’ grisaillerie continues afoot in Christopher Hartmann’s delectable Untitled (2024), offering a scene both quiet and chaotic. Waves of a previous, no doubt energetic exchange between two men ripple across a bed, undulating over compressed cushions and wrinkled sheets. This Still Life-cum-landscape painting is further embellished by a bed throw that meanders its way down the composition like a gushing stream of Kusama dots. However, the protagonists of Hartmann’s stage are the Calvin Klein underpants and socks strewn across the bed. Note the gaping holes fashioned by the tops of the socks and the large bulges that swell in the discarded underwear. More than relics of a heated moment, the clothes here assume the very actions their removal facilitated. Hartmann offers us a seductive stage, bathed in the night light of a bedside lamp that lends the painting an added erotic throb, yet the mood remains soft and thoughtful. Hartmann is an artist who transforms the abstract into the figurative, who turns a meditation on a fixed, objective moment into an extended consideration of an unfurling, subjective space. He is a painter who makes you as viewer, and his object as subject, feel at home even when the figure has come and gone, sounding silence; billowing stillness far, far away.

More abbreviations of the figure resound in the paintings of Rachel Lancaster. Arms Reach (2024) closes in on the back of a woman’s head and her neatly knotted hair. The painted surface is soft and milky, with an attention to volume – despite the image’s gentle haze – that recalls the Photopaintings of Gerhard Richter. Such gentleness of mood and application is then tested by the painting’s title. Arms Reach suggests a propensity for an action that, given the figure’s position with her back to us, can only mean an act of violence is about to unfold. That which felt supple now trembles. Shadow no longer models but worries the figure into a shushed stasis that questions the figure’s future well-being.

VI: HOME AND AWAY

This essay ends by looking at the work of Aaron Ford. A similarly soft serenity exhales from the two figures in his Two Women with Vases (2024), but the mood is here further antagonised by the artist’s liquid, inquisitive, slightly itchy line. Both sitters hold large vases: decorative yet utilitarian objects designed to hold celebratory bouquets of flowers, but which are empty. These vases are held close together by the sitter in orange, almost as if they are being protected, whilst the other sitter listens on her mobile phone. Both figures look down, somewhat solemnly, adding a perfume of melancholy to an air already heavy with hush. This atmosphere, humming with anticipation, thus reshapes the connotation of the vases. Rather than assume they are for flowers perhaps these vases function as urns, designed to contain the ashes of a loved one and the memories they hold for the sitters.

Ford’s portrait – the two sitters are real people, both friends of the artist – speaks to the dynamic and politics of family. Both women grew up in London but have families that are not British. Note the framed picture hanging on the wall occupying the top right corner of the composition. It is an original Iranian antique that belongs to the sitter – her name is Sarvin – seated on right and points proudly to her heritage. Just like this antique, the vase-cum-urns Sarvin so carefully protects thus becomes an act not just of memorialisation, but of generational maintenance: a passing of the family baton, so to speak. It is also worth noting Ford’s interest in depicting glass which, here, chimes materially with the vases. In many ways glass operates just like identity does: both provide lenses through which one can display or comprehend experience yet, of course, such experience is always fluid. Glass can reveal but it can also distort; it can offer clarity but can hoodwink the viewer with ripples of concave or convex otherness. Glass, like the antique and these vases, shows that the past always sits in the present and, here, it speaks to the future of these women living in a Britain that should welcome a kaleidoscope of otherness – in all its glorious colours – but often does not.

Family – born and chosen - brings us back to the very beginning of this essay and to the final analysis that notions of ‘home’ do not need to be understood in contradistinction to the language of ‘away’. People and families of all races, colours and creeds can co-exist in the same place and each can – and have the right to - call that place ‘home’. These artists’ shared focus on the figure cropped or abbreviated; fragile or fantastical; present or absent, shares such a vision. We are left with paintings that attempt to figure out Britain, but which are not just informed by a personal or national identity but are propelled by the greater force – and good – of humanity itself. And what is art’s role if not to hold up that glass of reflection to and for all of us and offer just a nibble of expression, confession and hope.

Matt Carey-Williams

Sandy Lane, Wiltshire

5-8 August 2024